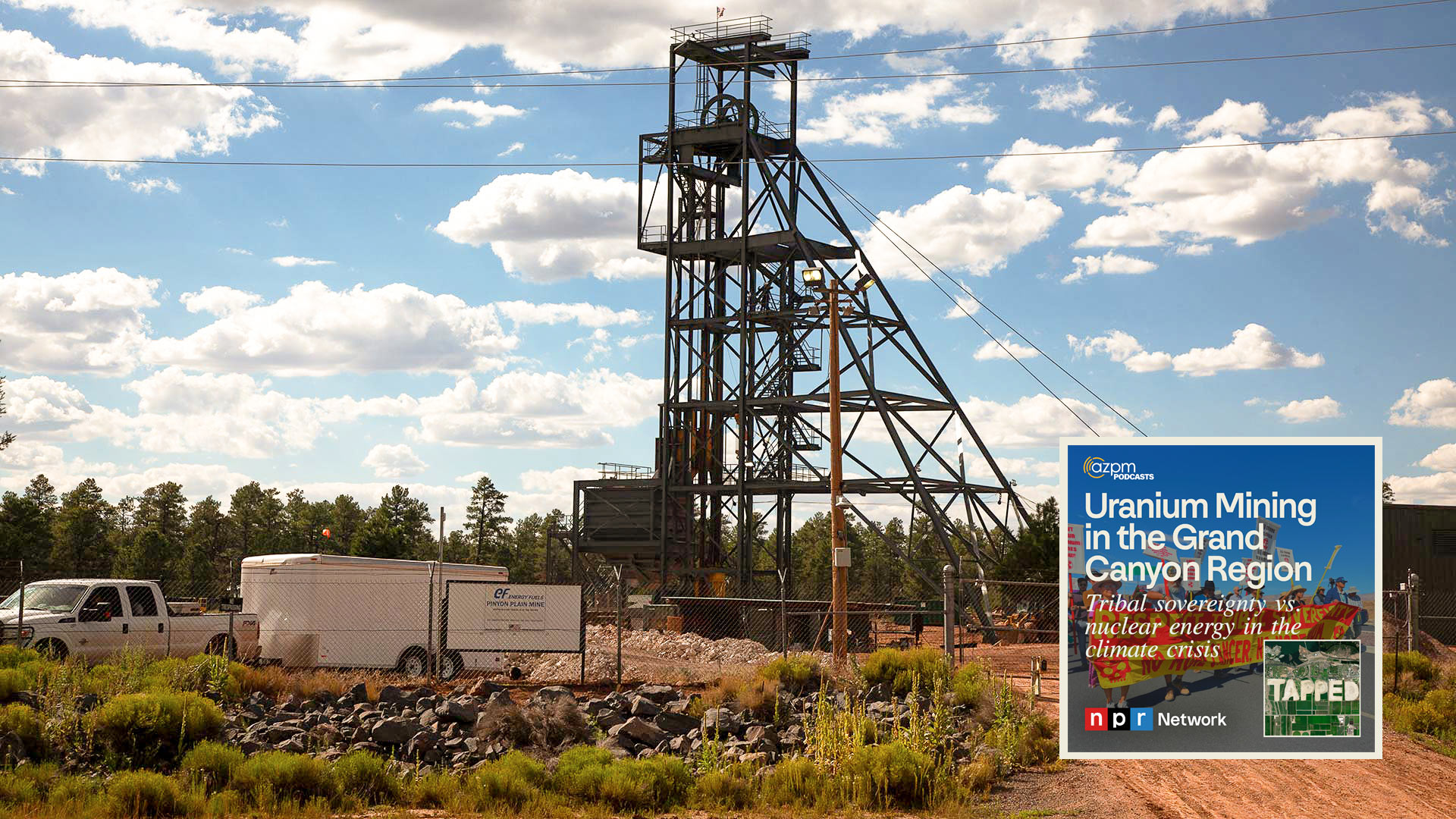

The Pinyon Plain Mine shaft in Coconino County, on Wednesday, Aug. 30. In 2016, the mine shaft punctured a perched aquifer that contained natural levels of uranium, requiring the mining company Energy Fuels to pump water to the surface to an impoundment for treatment.

The Pinyon Plain Mine shaft in Coconino County, on Wednesday, Aug. 30. In 2016, the mine shaft punctured a perched aquifer that contained natural levels of uranium, requiring the mining company Energy Fuels to pump water to the surface to an impoundment for treatment.

Tapped: Season 3 Episode 11

The costs of uranium mining and nuclear energy on Arizona's tribal nations are often hidden from the broader public. These communities are facing serious threats as their land and water resources become potential casualties in the pursuit of energy. We dive deep into the environmental, cultural, and historical impacts tied to the region’s most precious resource—water. Through expert interviews and firsthand accounts, we uncover how this issue challenges the survival of ecosystems, sacred sites, and the health of Indigenous communities, raising urgent questions about the future of water in the Southwest.

Transcript

Zac Ziegler: In the past few weeks, it's been hard to not think about climate change. A heat wave had most cities in the state breaking daily high-temperature records. Tucson hit 108 on September 28. Phoenix hit 117 that day.

Just a few days earlier, in the state's north, Flagstaff got two-tenths of an inch of precipitation in the form of overnight hail that didn't melt off until late morning. The city awoke to snow on the mountains that day, just before a historic heatwave would set in.

Then, there are conditions on the US East Coast, where a deadly hurrican wreaked havoc from Florida to North Carolina.

Katya Mendoza: As the weather gets more extreme, it's hard to not think about alternative fuels that don't produce greenhouse gasses. The sun goes down, and sometimes the wind doesn't blow.

Damming a river for its hydroelectric power has its own set of consequences

ZZ: Then there's Nuclear energy. It often sounds good, reliable, and at massive scale. But it's also hard to not think of devastating power: Three Mile Island, Chernobyl, Fukushima.

Paola Rodriguez: But nuclear is much more than just a tool or a weapon. It can be a solution to the world’s greatest problem: climate change.

With rising temperatures, finding solutions to issues like water accessibility and carbon emissions can compound itself when two similar interests collide.

ZZ: As countries add more clean energy, one question comes to mind: who gets to benefit from nuclear energy? Some political and environmental leaders will say everyone. But Arizona's tribal nations and their advocates would beg to differ.

This is Tapped, a podcast about water. I’m Zac Ziegler.

PR: I’m Paola Rodriguez.

KM: And I’m Katya Mendoza.

PR: A national monument meant to protect nearly one million acres of public lands is now facing legal pushback. The issue at hand: uranium mining.

KM: But how come leaders on both sides of the aisle are critical of the monument? And how does uranium mining at Pinyon Plain Mine reflect turmoil between two opposing needs: tribal sovereignty and climate change?

ZZ: Paola and Katya take it from here.

Sounds from Energy Fuels Inc. Corporate video: “Energy is such an important part of our everyday lives. Without access to clean affordable electricity and energy, you can’t have the modern society that we have today."

(audio ducks)

PR: This is a corporate video from Energy Fuels, a company that's been operating Pinyon Plain Mine in Arizona since 1986.

“...Energy drives just about anything. When you look at the various sources of energy, you really have to come up with the mix that fits the location and nuclear is about 20 percent of the power grid in the United States. The key with nuclear power right now is this focus on reducing carbon emissions. It’s going to play a major role in solving the climate change problem.”

PR: As climate disasters become more frequent and ever-rising temperatures, world leaders are looking for solutions. What can be done to consciously and feasibly slow down the climate crisis? For many countries, like the United States, nuclear energy is an attractive solution. Rafael Mariano Grossi, the director General of the International Atomic Energy Agency, said in an agency video that he believes that nuclear power is necessary for reaching net-zero emissions.

Sounds from IAEA Statement on Nuclear Power video: “Achieving sustainable economic development and averting the devastating consequences of unchecked climate change will require making use of all low carbon energy sources, including nuclear power. Studies confirm that the goal of global net zero carbon emissions can only be reached by 2050 with swift, sustained and significant investment in nuclear energy.”

PR: According to the U-S Department of Energy, nuclear energy can protect air quality by producing large amounts of carbon-free electricity. Currently, it provides power to communities in 28 states and plays a role in non-electric sectors like healthcare and space exploration.

Most notably, it is recognized as a clean energy source, with little to no greenhouse gas emissions.

But how clean is clean energy?

The Havasupai Tribe and environmental activists would argue not very, considering the impacts associated with mining materials like uranium.

(natural sounds of protests)

Dozens of protestors, led by Navajo Nation President Buu Nygren, First Lade Jasmine Blackwater-Nygren and other leaders, marched along the northbound lanes of Highway 89 in Cameron on Fri, Aug. 2, 2024 against uranium hauling through the reservation. The highway was part of the route taken by trucks from the Pinyon Plain Mine near the South Rim of the Grand Canyon three days earlier when they began uranium ore transportation through a large swath of the nation.

Dozens of protestors, led by Navajo Nation President Buu Nygren, First Lade Jasmine Blackwater-Nygren and other leaders, marched along the northbound lanes of Highway 89 in Cameron on Fri, Aug. 2, 2024 against uranium hauling through the reservation. The highway was part of the route taken by trucks from the Pinyon Plain Mine near the South Rim of the Grand Canyon three days earlier when they began uranium ore transportation through a large swath of the nation.

PR: In August, efforts to shut down Pinyon Plain–a uranium mine located about 7 miles south of the Grand Canyon, on the ancestral homelands of multiple tribal nations–continued.

NPR member station KNAU was there as activists and tribal leaders protested, sharing their fears of groundwater contamination.

(natural sounds fade)

Among the protestors there that day was Havasupai Tribal member Carletta Tilousi.

Carletta Tilousi: “We are only 756 tribal members. We are the original people of this land. We deserve protection. We deserve clean air and clean water, and that is our biggest voice and concern here…I think it's a matter of life, and that's what we're fighting for right now… If the tables were turned and this was happening to their communities, they would be concerned too. I guarantee you that.”

PR: The mine is owned and operated by Energy Fuels, a “Toronto-based company specializing in uranium and vanadium mineral exploration and development.”

Companies like Energy Fuels claim that industry practices have evolved and that efforts in remediation and reclamation have improved.

We asked Energy Fuels for an interview…either at one of their operations or online. They did not return our multiple calls or emails. Hence why you've been hearing audio from the company’s May 2023 corporate video.

Sounds from Energy Fuels Inc. Corporate video: “We’ve got a great record of environmental protection, regulatory compliance, worker safety. That’s probably the biggest misconception that people have. People think things haven’t changed in the last 70 years. Well, I’m here to tell you they have.”

PR: That is true– mining operations have adapted in recent decades, with stricter regulations and mandatory reclamation and remediation plans for companies undertaking exploration. However, these changes have been driven by historical injustices faced by communities neighboring the mines…including, in this case, tribal nations.

(music)

After the mid-1900s uranium mining boom, more than 500 mines were abandoned on the Navajo Nation. These mines eventually caused water contamination and health issues that have affected multiple generations. Leona Morgan with HaulNo!, an indigenous-led activist group opposing what they call ‘nuclear colonialism in the Southwest’, is determined to prevent any further mining on their lands in light of the challenges their communities have faced.

Leona Morgan: “Especially environmentally minded people, think nuclear is benign, and so when they don't see the front end of the nuclear fuel chain, the uranium mining, the milling, the processing, the transportation, they don't see us. They don't see the death and destruction and the sickness and all the harms it has caused.”

PR: For people like her, the return of uranium mining at Pinyon Plain leads to a renewed sense of invisibility.

LM: “No mining is safe…Companies will say what they want to say. But we, the people that live in these places, we can see the damage and we live and experience the results.”

PR: Some like Taylor McKinnon, the Southwest Director of the Center for Biological Diversity, believe that the push for nuclear energy doesn't outweigh the risks.

Taylor McKinnon: "The solution is solar, wind, battery, in places and transitioning away from the severely polluting fuels that are causing problems. Certainly, CO2 is a problem for climate change, but if you want to talk about the problems associated with the nuclear fuel cycle, I encourage folks to learn about the uranium mining legacy on the Navajo Nation, where we have several hundred uranium mines that date back 70 years that still haven’t been cleaned up, that still continue to pollute the land, the soil and the water that people there depend on and that’s one of the great injustices in American history…

PR: But is the groundwater of Arizona’s most remote tribal nation contaminated? The Havasupai Tribe resides in the Grand Canyon, with their ancestral homeland residing in where Pinyon Plain is.

In the last season of Tapped, we talked with Fred Tillman, a research hydrologist for the United States Geological Survey about the feasibility and probability of that concern. He said not right now.

Fred Tillman: “It could be if there were contamination from mine, it just hasn't reached one of the springs that we've sampled or one of the wells that we had access to. So it's one of those cases where it's very difficult to prove the absence of something, it could just be that it's on its way, and we just we weren't monitoring long enough yet.”

PR: According to the U-S-G-S, mines are not the sole source of uranium found in water; natural sources of uranium also exist in groundwater and springs fed by groundwater in the region.

Additionally, uranium isn’t the only element to consider in Northern Arizona.

FT: “...But, particularly with these, these mineralized breccia pipes where the uranium is found, there are other elements that you probably should be more concerned about one of them being arsenic, others meaning perhaps lead, or cadmium, or others that have an even lower MCL than uranium does.”

PR: The U-S Geological Survey still faces many unanswered questions like, “How does dust move uranium and other elements off mine sites throughout the mine life cycle, what are the effects of uranium and other elements on animals not yet studied, what is the source of uranium found in springs and groundwater, and what exposures occur during cultural use of resources.”

As the agency continues its studies, it is beginning to consider new perspectives that have never been acknowledged or recognized before.

Over the past two years, Carletta with the Havasupai tribe, worked with researchers including Jo Ellen Hinck to broaden the conceptual risk framework for uranium mining in the Grand Canyon Watershed to include the tribe’s perspective.

CT: “The elders every time they met with federal agencies and state agencies, they always talked about the contamination to the animals. They always talked about the contamination to the plants, and how when we gather the plants at Red Butte, we smell it. And you know, when we hunt the animals at the south rim of the Grand Canyon, we eat it.”

PR: Tribal members and dominant Western culture have different ways of living and different values, that are reflected in a varying sense of responsibility and the people they feel accountable to.

CT: “Every animal has a spirit, any every plant has a spirit, the wind has a voice, and the waters of all the elements of Mother Earth have a deity, and it is the responsibility of Native Americans to protect them.”

PR: Yet these perspectives have not been documented in U-S-G-S’s uranium research…until now.

CT: “It is a step in the right direction, and times when I feel like we're losing, we're also winning… sometimes I think about it like a chess game, you know, a chess game never ends. It doesn't end for a very long time.”

PR: Framework existed before but, according to the U-S Geological Survey, it “largely ignored exposure pathways relevant to Tribal communities in terms of traditional uses and existential values of the resources included.”

Now, the expanded framework includes exposure pathways like inhalation and ingestion from ceremonial practices, traditional foods, and medicines. Both the Geological Survey and Carletta hope that, by documenting and acknowledging tribal perspectives, this information will be used in federal research and decision-making for mining in the Grand Canyon Region.

CT: “We as Native Americans have been here for a very long time, and we're not going anywhere. And I think a lot of Americans forget the fact that we are original peoples of this lands and our voices, our existence, have been here for many, many years, and so it is important for us to maintain our identity, our culture, and our religious practices because that's all we have left now.”

ZZ: As research on uranium mining in the Grand Canyon progresses, the reality is that the mines are here to stay. We'll hear more after the break.

[break]

ZZ: This is Tapped, a podcast about water. I'm ZZ. We've heard about uranium mining's resurgence in Northern Arizona. Now, Paola and Katya tell us why it may be here to stay. Katya leads off.

KM: The U.S. Energy Information Administration says that the domestic uranium market will most likely grow between 2023 and 2024.

Between 2021 and 2023, more than 16 hundred exploration and development holes were drilled, marking the initial steps to uranium production. Companies are also expanding their operations.

In September, Energy Fuels announced the restart of mining operations at Nichols Ranch, a mine located 80 miles northeast of Casper, Wyoming. This mine is expected to begin operations as soon as the summer of next year.

The sudden demand for uranium is due to its rising price.

Earlier this year, uranium prices spiked at $106 dollars a pound. Now, the price of uranium is $82 dollars per pound, according to data from TradingEconomics.

The price is down, but it's still higher than it's been since the mid-2000s.

At levels not seen in decades, companies like Energy Fuels are trying to capitalize on the surge. which is why they started mining in the Grand Canyon region in December of last year.

There is also a national push to boost domestic supplies.

(news compilation of United States Russia's uranium)

Before President Joe Biden banned the import of Russian uranium earlier this year, Russia supplied 12% of the uranium used in the U-S. Canada, Australia, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan are all leading suppliers for the nation. Domestic uranium only accounts for 5% of the supply.

With the ban on Russian supplies in place, President Biden and national leaders are looking to tap into homegrown resources to make up the difference.

President Joe Biden: “The key to meeting the goal of 100 percent clean power grid by 2035 depends a lot on it. That’s why we’re keeping existing plants open, restarting shutter plants and build America’s first new nuclear plants in decades.”

KM: Energy Fuels says that the uranium ore found within the Pinyon Plain Mine could produce enough carbon-free green energy to power the entire state of Arizona for over a year.

Sounds from Energy Fuels Inc. Corporate video: “It has the equivalent amount of energy as would be contained in a train that had coal that stretched from Los Angeles all the way to New York and part of the way back again, the amount of electricity contained on this small, 14-acre side of land is quite extraordinary.”

KM: If a 14-acre parcel can produce that much energy, imagine the potential of more extensive exploration.

Despite the rising demand, new uranium mining claims cannot be filed in the region due to last year’s designation of the Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni- Ancestral Footprints of the Grand Canyon National Monument.

Republican lawmakers in the state, including Senate President Warren Petersen, argue that the restrictions imposed by the National Monument will have a devastating impact on the economy…

WP: “And our national security, devastating critical industries like mining and cattle ranching…Frankly, we don't need or want the federal government coming in and dictating to Arizonans how to protect Arizona. We know better than Washington, what is best for our lands and our citizens. This federal overreach is completely unacceptable and unconstitutional…”

KM: Petersen, along with other Republicans, is currently suing Biden’s administration calling the monument a, “dictator-style land grab”.

Taylor argues that Biden’s designation of the Grand Canyon National Monument is strong in safeguarding nearly one million acres of public land that surrounds the iconic national park, including the sacred ancestral land of the Havasupai Tribe.

TM: “The President was squarely within his purview under the Antiquities Act to protect that place for all of the values that it harbors.”

KM: Petersen is not alone in his dissatisfaction with the monument. Co-founder of the anti-uranium mining group; Leona calls it a “complete failure”.

LM: “Sure it stopped a few thousand claims that have not been developed under the 1872 mining law, but it allowed for this gaping loophole, which advances Pinyon Plain uranium mine, and there's a handful of other mines that have this, what's called valid existing rights.”

KM: Taylor is somewhat more hopeful about the designation’s impacts.

TM: “One of the reasons that the monument was designated was to protect groundwater and surface water that’s so critical to our region’s people and biodiversity and insofar as there’s a mine that wasn’t stopped by the monument, we need to finish the job of providing for those protections. The same values that the monument was designated to protect are now under immediate threat from mining that’s occurring right now at the Pinyon Plain Mine.”

KM: These values are the reason why groups like the Center and Arizona’s northern tribal nations are rallying together to protect what matters most to them…life.

LM: “Water is life. Water is not just life for us humans, but also, of course, the plants and the animals, but also water itself is a sacred entity, and we need to protect water. We need to protect our sacred entities. We need to protect all of our non-human relatives.”

KM: Leona implied that this fight is far from over and has the potential to impact many more around the world.

LM: “This energy fight, it's not just nuclear. It's coming because of climate change, a lot of indigenous people around the world will be dealing with new proposals for lithium mining and different types of extraction that have similar impacts. It might not be radioactive, but it will contaminate the water, and then that gets in our body, and then we get sick, and that goes on to our babies, and so this needs to stop.”

KM: In June, environmental groups like HaulNo!, the Center for Biological Diversity and leaders from the Havasupai Tribe submitted a petition with 17,000 signatures to Governor Katie Hobbs asking her to shut down the Pinyon Plain Mine.

Sandy Bahr, director of the Grand Canyon Chapter of the Sierra Club (left) and Carletta Tilousi, Havasupai tribal member and leader (right) hand off over 17,000 petition signatures to Governor Katie Hobbs, urging her to shut down the Pinyon Plain uranium mine outside of the Grand Canyon on Thursday, June 27, in Phoenix, Ariz. This follows a letter sent to the governor earlier this year, which requested her action to limit the mine's activities to closure and maintenance activities.

Sandy Bahr, director of the Grand Canyon Chapter of the Sierra Club (left) and Carletta Tilousi, Havasupai tribal member and leader (right) hand off over 17,000 petition signatures to Governor Katie Hobbs, urging her to shut down the Pinyon Plain uranium mine outside of the Grand Canyon on Thursday, June 27, in Phoenix, Ariz. This follows a letter sent to the governor earlier this year, which requested her action to limit the mine's activities to closure and maintenance activities.

Taylor says that the petition follows a letter that was sent by dozens of environmental groups earlier this year asking her to close the mine.

TM: “This is the Grand Canyon. This is our state’s namesake and our state’s governor needs to assert leadership and close this mine down…Permanent pollution of Grand Canyon’s aquifers is not a risk that we should be taking.”

VIEW LARGER Sandy Bahr and environmental advocates protesting the Pinyon Plain uranium mine at Governor Katie Hobbs' office in Phoenix, Ariz., on Thursday, June 27. Bahr, director of the Grand Canyon Chapter of the Sierra Club alongside the Center for Biological Diversity, HaulNo! and other environmental advocacy groups dropped off over 17,000 petition signatures to the governor, urging her to close the mine located in the Grand Canyon region.

VIEW LARGER Sandy Bahr and environmental advocates protesting the Pinyon Plain uranium mine at Governor Katie Hobbs' office in Phoenix, Ariz., on Thursday, June 27. Bahr, director of the Grand Canyon Chapter of the Sierra Club alongside the Center for Biological Diversity, HaulNo! and other environmental advocacy groups dropped off over 17,000 petition signatures to the governor, urging her to close the mine located in the Grand Canyon region. KM: The tensions between Energy Fuels and Northern Arizona tribes have only escalated.

This summer, Navajo Nation President Dr. Buu Nygren took action, deploying Navajo Police to stop uranium shipments that violated tribal laws. Energy Fuels had failed to give a two-week notice—a move Nygren called a “blatant disregard” for Navajo sovereignty. Now, all parties have agreed to a voluntary pause on uranium transport until negotiations are completed.

But the conflict doesn’t stop there. Governor Katie Hobbs is urging the U-S Forest Service to conduct a supplemental review of the decades-old Environmental Impact Statement for the Pinyon Plain Mine. This follows Arizona Attorney General Kris Mayes’ formal request for a new assessment, highlighting the growing concern over the mine’s potential threat to Arizona’s groundwater.

In response, the Forest Service said it would conduct an interdisciplinary review and compile its findings in a supplemental information report.

ZZ: So, how far does this battle over uranium mining go? What are the hidden costs as companies push for nuclear energy? And with the West already grappling with dwindling water supplies and rising temperatures, who stands to benefit from this renewed focus on "clean" energy? Next time, Katya and Paola uncover the full extent of uranium’s impact on the Navajo Nation and dig into the deeply rooted mistrust Navajo families have—not just towards mining companies but also the federal government’s long history of uranium prospecting.

(theme music fades in)

Tapped is a production of AZPM News.

This episode was written and produced by Paola Rodriguez and Katya Mendoza, with mixing by me, Zac Ziegler.

Editing by me and our news director, Christopher Conover.

Our theme music is by Michael Greenwald.

Visit our website in the podcast section of azpm.org for pictures, links and more. Thanks for listening.

(theme music fades out)

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.