An irrigation canal carries Colorado River water to crop fields in central Arizona.

An irrigation canal carries Colorado River water to crop fields in central Arizona.

Declining flows in the Colorado River could force Southwest water managers to confront long-standing legal uncertainties, and threaten the water security of Upper Basin states of Colorado, Wyoming, Utah and New Mexico, according to a new analysis.

A new paper by Anne Castle at the University of Colorado-Boulder and John Fleck at the University of New Mexico identified many risks facing the basin. These risks need to be addressed in order to avoid disaster for the Colorado River, a water source relied on by more than 40 million people in the southwestern U.S. and Mexico, the paper’s authors wrote. (Some of Castle’s work receives funding from the Walton Family Foundation, which also supports KUNC’s Colorado River coverage)

Much of the risk lies in the relationship between the river’s two basins. Ambiguity exists in the language of the river’s foundational document, the Colorado River Compact. That agreement’s language remains unclear on whether Upper Basin states, where the Colorado River originates, are legally obligated to deliver a certain amount of water over a 10-year period to those in the Lower Basin: Arizona, California, and Nevada.

According to that document, each basin is entitled to 7.5 million acre-feet of water, with the Lower Basin given the ability to call for its water if it wasn’t receiving its full entitlement. That call could result in a cascade of curtailments in the Upper Basin, where cities and farmers with newer water rights would be shut off to meet those downstream obligations. That’s a future scenario water managers need to acknowledge and plan for, Castle argues.

“We think the risk is very real,” Castle said at the Upper Colorado River Water Forum at Colorado Mesa University in Grand Junction. “We think it’s significant, particularly when you factor in the legal uncertainties and the hydrology that we’ve already experienced in the 21st century.”

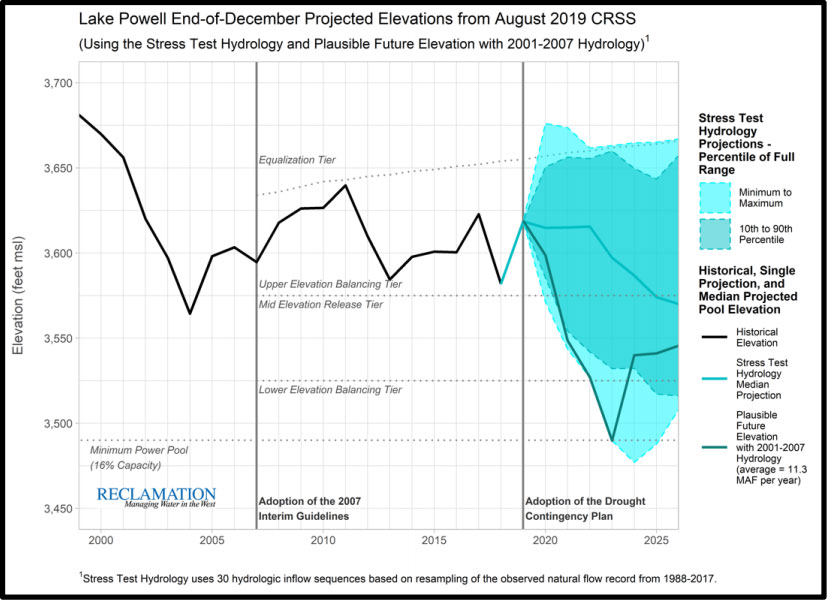

Back in the early 2000s the Colorado River basin saw one of its driest periods on record. Castle and Fleck’s analysis suggests that if that the dry period from 2001 to 2007 were to repeat, within a few years the river’s biggest reservoirs would decline so rapidly that the threat of a Lower Basin call would become much more real.

VIEW LARGER A graph that explores future elevations in Lake Powell under certain scenarios, from Castle and Fleck's paper.

VIEW LARGER A graph that explores future elevations in Lake Powell under certain scenarios, from Castle and Fleck's paper.

In the long term, Castle said, the risk grows even higher. Layer on climate change models, which project that the river will likely experience significant declines in coming decades, and “things get pretty serious pretty quickly,” Castle said.

Much like the calculation of whether or not to buy insurance to hedge against a catastrophic or costly loss of home, car or health, Castle said the Upper Basin states need to fully explore what kinds of risks they’re facing when it comes to water supplies from the Colorado River.

“In order to decide whether you want to buy an insurance policy and how much you want to pay for it,” she said. “You need to know what the risk is that you’re insuring against.”

One option to manage that uncertainty has taken the form of demand management, a conceptual plan the states are currently exploring. In its basic form, the program would pay water users -- farmers, cities or industries -- to forgo their use to boost reservoir storage in Lake Powell. Colorado, the state furthest along in crafting a demand management program, has formed nine work groups to examine the thorniest questions it brings up.

If leaders in the river’s Upper Basin states choose not to come up with a plan to manage that risk, Castle said, future scarcity could lead to rampant litigation among the states, and increase uncertainty about the Southwest’s water supplies.

This story is part of a project covering the Colorado River, produced by KUNC and supported through a Walton Family Foundation grant. The project is solely responsible for its editorial content.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.