Brad Lancaster harvesting mesquite.

Brad Lancaster harvesting mesquite.Production of "Feeding Our Future" is made possible with the support of the Zuckerman Family Foundation.

Just before the monsoon rains, it’s time for the mesquite trees to start dropping their long, cream-colored pods. It’s also time for Brad Lancaster to spread the love of mesquite to the people of Tucson.

Brad Lancaster is co-founder of Desert Harvesters. “We’re a local nonprofit that’s all about promoting the growing, harvesting, processing, enjoying and celebrating of local, wild, native foods,” he explains, chewing on a freshly-picked mesquite pod.

“Mmmm! This one is sweet! Not like candy-bar sweet, but sweet!”

There are more than 400 wild, native foods in the Sonoran Desert. Today, Lancaster and other Desert Harvesters are at the Las Milpitas de Cottonwood Community Farm. It’s west of I-10 and south of 29th Street, along the Santa Cruz River. Lancaster shows a group of teens from City High how to harvest mesquite pods. He snaps a few off a branch and hands them around, warning:

“Some are heinous. The key thing is, you taste before you pick. You can get bitter, chalky, drying.”

“It feels like a cotton ball just exploded in my mouth,” says a tenth grade boy, looking pleased.

“You do not want to pick that one!” Lancaster advises. “You can get apple flavored, nutty. Boom! There’s lunch! We got a favorable flavor sample on this one. Trees growing in your yard, along your street -- it’s a free harvest! They thrive – for free!!”

“We are surrounded by these incredibly abundant food forest, but nobody sees it!” -- Brad Lancaster

The Desert Harvesters take their hammermill to neighborhoods and festivals. The dried mesquite pods go in the hopper and come out the other end as flour.

The Desert Harvesters take their hammermill to neighborhoods and festivals. The dried mesquite pods go in the hopper and come out the other end as flour. He takes the group to a few more trees to sample the pods. He points out that some trees grow pods in bunches, which means they’re easy to harvest by the handful.

“We are surrounded by these incredibly abundant food forests,” says Lancaster. “But nobody sees it! They just think, ‘Oh that’s just desert scrub. There’s no use.’ ”

Not only are wild, native foods free, but they are nutritious. Cholla cactus buds, prickly pear fruit, wild spinach, chia seeds and mesquite flour help regulate blood sugar. Lancaster says there’s also an economic opportunity here. More and more restaurants in Tucson want to put local, native foods in their menus.

“But we don’t have the harvested supply to meet the growing demand,” says Lancaster.

Mesquite flour sells for $14 a pound, and up. An enterprising harvester can walk through nearly any park in Tucson and collect bucketfuls of pods. Desert Harvesters teaches workshops to low-income people through the Community Food Bank of Southern Arizona (Las Milpitas is the food bank’s farm). Lancaster says the idea is “to get more people knowledgeable. This becomes an income source for them.”

It’s free food growing on a tree that doesn’t need irrigation.

Brad Lancaster co-founded Desert Harvesters and teaches workshops on how to identify, harvest and prepare wild native foods.

Brad Lancaster co-founded Desert Harvesters and teaches workshops on how to identify, harvest and prepare wild native foods.

On the other side of Las Milpitas, Desert Harvester volunteers are running the grain mill. It’s loud. Most people don’t just munch on whole mesquite pods; they turn it into flour and cook with it. Lancaster gives the City High kids a sample to taste. He reminds them that the flour flavor will differ depending on the tree they picked from.

The mill is mounted on a trailer so Desert Harvesters can take it around to neighborhoods and farmers markets during harvest time. The group tries to make it easy for people to turn their pods into flour and take advantage of this free food. But Lancaster says most people don’t know what to cook with mesquite. Even he didn’t have much of a mesquite flour repertoire. “We’d just been makin’ pancakes!” he says.

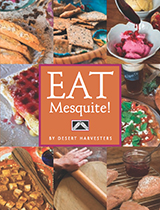

So Desert Harvesters asked people for recipes and put together the Eat Mesquite cookbook.

“You can make cakes, breads, pie crust, pizza, ice cream, mole, baklava, tamales, Indian naan bread with prickly pear chutney,” Lancaster tells the high school students. “When you get a little older you can make beer.”

What gets him most excited about mesquite is not just that it’s free food growing on a tree, but that it’s free food growing on a tree that doesn’t need irrigation. “No water bill! They’re already are doing great with rainfall. That’s what they’re adapted for!”

Lancaster literally wrote the book on rainwater harvesting. It’s called Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond. Rainwater harvesting is simply techniques to collect, store and use rainwater. At his house in the Dunbar/Spring neighborhood, the land between people’s property lines and the street was bare dirt. Lancaster and his neighbors dug basins and planted natives like chollas and mesquites in those basins. Then they made cuts in the curb. Now, when it rains, the storm water rushes down the street and goes right into those basins, and fills them up.

The pods from every mesquite tree have different flavors. Brad Lancaster recommends tasting before you pick. He says some can be “heinous,” while others can be as sweet as candy.

The pods from every mesquite tree have different flavors. Brad Lancaster recommends tasting before you pick. He says some can be “heinous,” while others can be as sweet as candy.

“It had gone from this completely denuded walkway to this beautiful canopy that was cool and you could have native fruits being produced whether it was cholla buds or the mesquite pods,” says Leslie Ethen. She is Sustainability Manager for the City of Tucson, in the Office of Integrated Planning.

“When I hear about sustainability, something that frustrates me,” says Lancaster, “is what are we trying to sustain? Because the system we currently have consumes more water than it generates. It consumes more fertility than it generates. I like the idea of a regenerative system. So how do we grow food in a way that enhances our health, the health of our soil, the health of our watershed and the health of our economy?”

Ethen says, “Brad Lancaster’s house opened my eyes to the real potential that water harvesting – just passive water harvesting -- could have in our community.”

What will happen to native plants when our region heats up? The University of Arizona’s Climate Assessment for the Southwest (CLIMAS) predicts a 10-percent drop in annual precipitation in the next decade, and a later start to the monsoon rains.

“Desert plants and trees will probably survive,” says Ethen, “but they’ll be under a lot more stress, which makes them more susceptible to things like pests and fire.”

More bad news from CLIMAS: the temperature is predicted to be a lot hotter, with more days that break 110 degrees.

“When I think about Tucson’s food system, the first and foremost alarm bell is water,” says Ethen. “In a non-desert environment having as much of your food produced locally is key. When you live in the kind of environment we do and when climate change is posing such a risk to our water supply it’s not so cut and dry – or maybe I should say wet and dry.”

Is local food production the best investment of our water?

“We don’t necessarily have to grow Midwest corn,” says Ethen. “Are there more desert-adapted varieties? Does it make sense to bring it in from elsewhere? I talked to a climate scientist who frankly advocates for importing our food because we’re importing that water, too.”

A Saudi company had that same idea. In January 2016, Almarai bought 14,000 acres of farmland between Gila Bend, Arizona and Blythe, California. They’re growing alfalfa, and shipping it back to Saudi Arabia to feed dairy cows. Alfalfa needs a lot of water.

Gary Nabhan is Director of the Center for Regional Food Studies at the University of Arizona. He is a strong advocate for supporting our local food system.

Gary Nabhan is Director of the Center for Regional Food Studies at the University of Arizona. He is a strong advocate for supporting our local food system. “They are saying that they are protecting their capacity for future self-sufficiency by not pumping their groundwater and getting their alfalfa from someplace else,” says Gary Nabhan, director of the Center for Regional Food Studies at the University of Arizona.

But Almarai is pumping Arizona’s groundwater. “Groundwater pumping is as much extraction as much as mining copper or coal,” says Nabhan. “It’s absolutely legal—they’re doing nothing wrong illegally -- but is it morally okay to deprive future generations of Arizonans of water to export crops for another country?”

Right now, 98 percent of our food comes from outside our region . . . There’s something like a three-or-four-day supply of food in the community at one time.

And what happens if the people of Mexico and California start to ask the same question about their water being exported to Arizona in the form of tomatoes and all the other food the supply us with in Southern Arizona? Nabhan says we need to be prepared for these conversations, and we need to strengthen our local food system.

What tastes good with mesquite flour? Desert Harvesters put together a cookbook.

What tastes good with mesquite flour? Desert Harvesters put together a cookbook. “I don’t expect everyone to eat mesquite pods and cholla buds,” he says “but I do wish that everyone could see that the desert is not the limiting factor to us gaining local food security and health for our children.“

Right now, 98 percent of our food comes from outside our region, according to Leslie Ethen. She says Tucson Water is preparing for the future by banking around six months of water supply from the Central Arizona Water Project (CAP) each year. But when it comes to food, we don’t even have a one-week’s supply.

“There’s something like a three-or-four-day supply of food in the community at one time,” she says. “Those are the things we need to think about, and it isn’t just about putting food on someone’s table now; it’s being able to plan to withstand those larger-scale disruptions.”

She says there’s no plan -- yet -- from the City or County for long-term food security, “but you’ve got a lot of really passionate and smart planners who have this on their radar screen and are thinking about it every day and looking for ways to just slowly move the needle.”

Leslie Ethen says climate change probably won’t hit Arizona as a single, catastrophic event like a Hurricane Katrina. It’ll be more like death by a thousand cuts – on an endless summer of 116-degree days and no rain on the horizon. But Ethen believes we still have time to get ready.

Tune in to Arizona Spotlight or log on to AZPM.org next week for "Feeding Our Future, Episode 6: Turning Garbage into Gardens". Next week, on NPR 89.1.

Click below to hear more about the Kino Heritage Fruit Trees Project at Mission Garden, with Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum Education Specialist Jesus Garcia.

Click below to hear more about the Kino Heritage Fruit Trees Project at Mission Garden, with Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum Education Specialist Jesus Garcia.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.