Ragged Top Peak in Ironwood Forest National Monument.

Ragged Top Peak in Ironwood Forest National Monument.

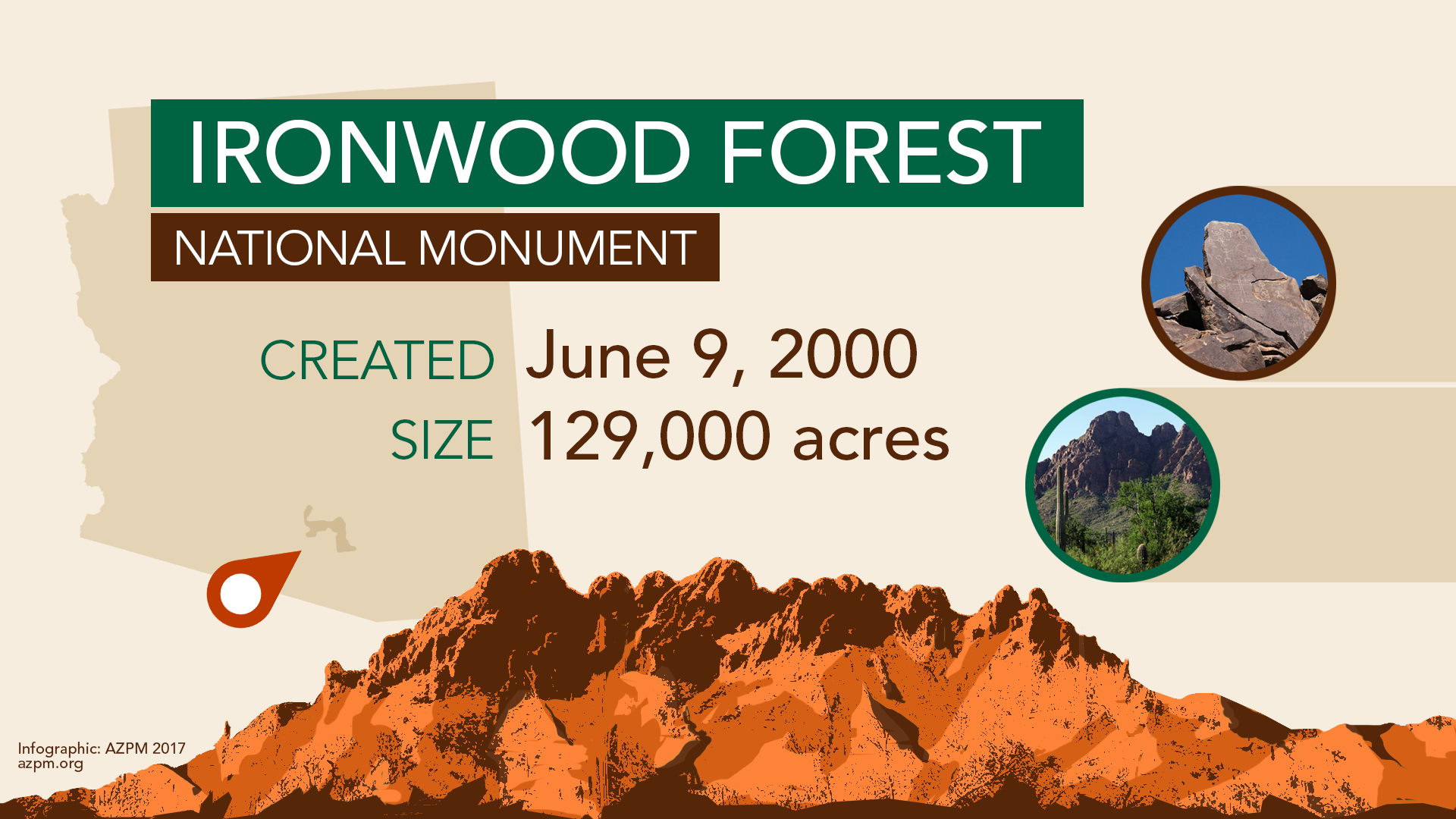

Ironwood Forest National Monument sits northwest of Tucson and has an odd shape on maps, like a Tetris piece. Perhaps not as photogenic as Utah’s Grand Staircase-Escalante, nor as controversial as Bear’s Ears in the same state, Ironwood landed on a list that called into question the status of those and 24 other monuments around the country.

The site is 129,000 acres of desert and jagged mountains. Designated in 2000 by then-President Bill Clinton, its future became a question mark this April when President Donald Trump signed an executive order asking the Department of the Interior to review certain monuments and determine if they should be eliminated or downsized.

VIEW LARGER Ironwood Forest National Monument was established in 2000.

VIEW LARGER Ironwood Forest National Monument was established in 2000. The review put in the crosshairs any monument over 100,000 acres designated after 1996. As of Thursday, Aug. 24, Ironwood’s fate was still not clear. Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke that day said no monuments would be eliminated, but that he would recommend shrinking some.

Conservation groups all over the country criticized the review and its implications, and advocates for Ironwood Forest National Monument were no exception.

Representatives from from environmental groups, political leaders like U.S. Democratic Rep. Raúl Grijalva, and Tohono O’odham Vice Chair Verlon Jose called for the continued protection of the monument, while three Republican U.S. representatives from Arizona, including Paul Gosar, urged its closing.

Arizona Public Media recently visited the monument to better understand its origins and what’s at stake with the review.

Getting there

Four people opposing any changes that would reduce Ironwood Forest National Monument’s size gave us a tour.

Carolyn Campbell, the executive director of the Coalition for Sonoran Desert Protection, said that in the late 90s overlapping interests converged to lead to the monument designation. Conservation groups wanted to protect desert flora and habitat for species like the cactus ferruginous pygmy owl. Homeowners in the area of the Silver Bell mountains wanted the county to protect the land there, and originally envisioned a county mountain park.

VIEW LARGER Carolyn Campbell, Executive Director of the Coalition for Sonoran Desert Protection

VIEW LARGER Carolyn Campbell, Executive Director of the Coalition for Sonoran Desert Protection Those interests found common cause with ongoing efforts to protect cultural sites, she said, like Los Robles Archeological District, the Mission of Santa Ana del Chiquiburitac and Cocoraque Butte, all of which are inside Ironwood Forest National Monument.

“When it was more well known that the federal administration was pushing the BLM lands to have this special status, that’s when we went to the interior secretary, and said, ‘Can you designate this as a national monument?’”

She was referring to then-Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt. Campbell said that at the time Babbitt was pushing to change the culture of the Bureau of Land Management to include conservation. Pima County was making its own culture shift, she added, with the Sonoran Desert Conservation Plan.

“So there were all these different pieces that were pretty special.”

A Harris's Hawk perches on a saguaro cactus in Ironwood Forest National Monument, with Ragged Top Peak in the distance.

A Harris's Hawk perches on a saguaro cactus in Ironwood Forest National Monument, with Ragged Top Peak in the distance.

Underneath Ragged Top

Ragged Top Mountain is likely the most iconic image in Ironwood Forest, characterized as a “biological and geological crown jewel” in the proclamation. The Wilderness Society’s Mike Quigley said it’s a lambing area for an indigenous herd of bighorn sheep. Conservation groups cite that herd’s protection as part of the importance of Ironwood Forest National Monument.

The monument status is vital for the health of the herd, Quigley said, as sheep are under high metabolic stress during lambing season.

And a monument’s status does more than just protect core habitat for wildlife in such a place, he said.

“I think one of the values that a national monument brings to a place is it actually gives it a name and a literal place on a map,” Quigley said. “So when the new maps are printed, the boundary of Ironwood Forest shows up, the name is right there on the map, similar to Saguaro National Park and other really treasured public lands that other people seek out to go visit.”

At issue for some who support the downsizing of the monuments is the question of multi-use lands. I asked Quigley: Who uses the monument?

“You mean besides wildlife?” he joked.

“So really, everyone uses it. There’s cattle grazing here, we see signs of that in the wash. It’s open for hunting. It’s a good place for hunting. Recreational groups … folks come out to camp. … Researchers like Kelsey.”

VIEW LARGER Kelsey Yule reaches up to examine some mistletoe in Ironwood Forest National Monument.

VIEW LARGER Kelsey Yule reaches up to examine some mistletoe in Ironwood Forest National Monument. Kelsey Yule is a Ph.D. candidate in ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Arizona. She’s also on the board of Friends of Ironwood Forest, a group advocating for its protection. Her work on desert mistletoe brought her to the monument. She has other reasons to come.

“Honestly I think a big draw and what makes me love the Ironwood is how little development there is, how few well-traveled paths there are and how few cars you run into on a normal day out here. So that means that you see a lot more, I think.”

Campbell, Quigley and Yule talked about the ironwood tree. According to the proclamation, the Silver Bell Mountains are home to the highest density of ironwoods in the Sonoran Desert. It blooms lavender, can live for hundreds of years, and acts as a nurse tree for other plants and cactus, cooling them in the summer and preventing damage from the cold in the winter.

“Saguaro is a really good example. Eventually they tower over the ironwood,” Campbell said. “Plants, small mammals, birds — they just really depend on the tree. It’s a very very unique tree and it’s a very unique habitat. I mean, it’s our old growth forest.”

The other side of the monument

Many who voiced support for Trump’s monument review cited federal overreach, calling foul on the use, or what they say is misuse, of the Antiquities Act in designating the protected space. Most designations must come from Congress, but the 1906 act allows presidents to unilaterally create monuments.

An old, broken down ironwood tree.

An old, broken down ironwood tree.Quigley says the Grand Canyon is a good example of why the Antiquities Act is important. Teddy Roosevelt dedicated it a monument in 1908, years before Congress recognized the value of preserving it and turned it into a park, he sad.

Not all people see it that way.

In public comments submitted during the review, Southern Arizona Business Coalition Vice President Rick Grinnell signed a letter with three other groups, including the Arizona Mining Association, calling for the reduction of size of Ironwood Forest National Monument.

He said the monument goes beyond the intended parameters of the 1906 Antiquities Act.

“You’re talking about the expansion under the environmental supporters, if you will, the expansion under the Antiquities Act was very specific in what it says: Historic and archaeological sites and objects. Period.”*

In the case of Ironwood Forest National Monument, that would include sites like Los Robles and Cocoraque Butte.

Grinnell sad he’s not against the monument, but he estimates that a reasonable review could lead to downsizing the monument to about 14,000 acres, instead of the current 129,000, to protect only the archeological and historically significant sites.

“What is the repercussions and what is the impacts of taking land from the private owners, agriculture, cattle, mining, potential development?” he asked.

Grinnell said there’s untapped economic potential there, especially from mining.

There is mining in the area. The Silver Bell Mine existed before the designation of the monument, and continues to extract copper, just at Ironwood’s boundary. The monument also sports evidence of grazing, and we ran into few head of cattle on our visit.

While it’s not clear what kind of additional wealth in copper or other industries lies within the current boundaries of Ironwood Forest National Monument, Grinnell said the protections shut down any potential industry and cost the state important economic growth and jobs that wouldn’t harm wildlife.

“There’s no proof that mining or ranching or … agriculture deter this wildlife from existing. Wildlife and mining has coexisted for well over centuries,” he said. “Let’s be reasonable about what should be designated national [monument] and what shouldn’t.”

The Wilderness Society’s Quigley said such a discussion calls up choices that must be made about public lands.

“We can dig copper out of the ground, or we can use them for recreation value, for conservation value, and we need to find that balance,” he said. “Think of it as a portfolio approach to managing our public lands. No prudent investor goes all in on the high-risk destructive single-use category.”

Grinnell offered that mining has “abused resources” in the past, but said that’s not a problem anymore. He said further mining operations would occupy a “very small” area compared to the expanse of desert there, citing the “small footprint” of the current Silver Bell Mine.

“You can go out there for miles and miles and miles and not see anything,” Grinnell said.

*Language in the Antiquities Act also includes objects of “scientific interest.”

Common ground

Arizona Public Media found overwhelming support for protecting Ironwood Forest in a sample of comments submitted to the Interior Department. A poll conducted by the Morrison Institute for Public Policy, before Trump’s executive order, suggested a majority of Arizonans are in favor of conserving natural resources, even if it means slower economic growth, the Arizona Republic reported.

“I’ll respect their opinions,” Grinnell said, but called such concerns “overly emotional and less based on fact.”

On our last stop in Ironwood Forest, we visited Cocoraque Butte, one place everyone we spoke to agreed should be protected by the monument.

Bob Hernbrode is retired from a career as a biologist in wildlife management. He served one term as Arizona Game and Fish Commissioner.

VIEW LARGER Bob Hernbrode is a former Arizona Game and Fish Commissioner.

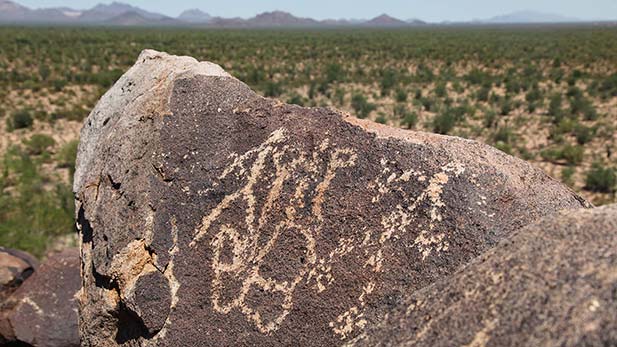

VIEW LARGER Bob Hernbrode is a former Arizona Game and Fish Commissioner. While not a geologist or an archeologist, he helps his wife Janine, who leads a group of volunteers working on a comprehensive inventory of petroglyphs at this site, an endeavor he said is sponsored by the Arizona State Museum.

That group, he said, has recorded between 1,800 and 1,900 hundred images of artifacts at Cocoraque Butte.

“The petroglyphs range from modern, to historic, to Hohokam, to probably pre-Hohokam stuff. Some of the petroglyphs are so repatinated to the point that you don’t even see them unless the light is right. And that’s why we did a comprehensive, so you can begin to see that,” Hernbrode said.

He stopped to point out the various fresh tracks of animals, snakes and deer. Very quickly we found a sherd of pottery and a sharp, fashioned point. They are found all over the site, and only increase as one approaches Cocoraque Butte.

“It’s a huge big boulder pile of boulders that are anywhere from basket size to Volkswagen size, and there are petroglyphs scattered from top to bottom on this site, that range in age probably from nearly 2,000 years old —probably the most of them are in that area between [the years] 1150 and 1400 or thereabouts. All the way to the top, are petroglyphs.”

The team is working to create a comprehensive inventory to give to the BLM, and to the Arizona State Museum, to increase understanding of Cocoraque Butte, it in hopes to aid its protection, against things like vandalism.

“We think, ‘How could anybody live here?’ But people lived here for hundreds of years, thousands of years probably.”

As of Thursday afternoon, there were no details about the recommendation for Ironwood Forest National Monument. That day, Carolyn Campbell, of the Coalition for Sonoran Desert Protection, said her office was “on pins and needles" waiting for news on the monument.

AC Swedbergh contributed reporting to this story.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.