Lake Mead seen from an airplane.

Lake Mead seen from an airplane.

Federal officials recently issued a grim forecast for the Colorado River. After a winter with very little snow in the Rockies, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation says there's more than a 50 percent chance that Lake Mead will fall into shortage in 2020. That's ramping up pressure on Lower Basin states to sign on to a plan to reduce their water usage. AZPM's Vanessa Barchfield teamed up with the Arizona Daily Star's Tony Davis to explore what the plan is, and why Arizonans — in particular — should care.

A bruising battle between the Central Arizona Project and many states and water users has revitalized the push for a stillborn plan to prepare for more drought on the Colorado River.

The original dust-up was over whether the CAP was seeking to “game the system” of reservoir operations at lakes Mead and Powell to benefit itself at the expense of the river’s Upper Basin states: Utah, Colorado, New Mexico and Wyoming.

That’s prompted new talks to try to also resolve longstanding differences with another of CAP’s adversaries, the Arizona Department of Water Resources.

The hope is that this will lead to approval by year’s end of a proposed Drought Contingency Plan for the Lower Basin states of Arizona, Nevada and California, to conserve more water now to prevent catastrophic declines at Lake Mead later.

At stake is the future of your drinking water supply — the CAP’s canals bring river water to Phoenix and Tucson — and that of the 40 million people in seven states and Mexico who also depend on the Colorado River for water.

Six things to know about this future:

1. President Trump has called concerns about human-caused climate change bad science. But out West, his Bureau of Reclamation officials are saying the seven basin states must act to avert a crisis on the Colorado that many scientists have traced to climate change.

Last Tuesday, Reclamation Commissioner Brenda Burman and bureau official Terry Fulp made their strongest warnings yet to the Imperial Irrigation District’s governing board in El Centro, California, just west of Yuma.

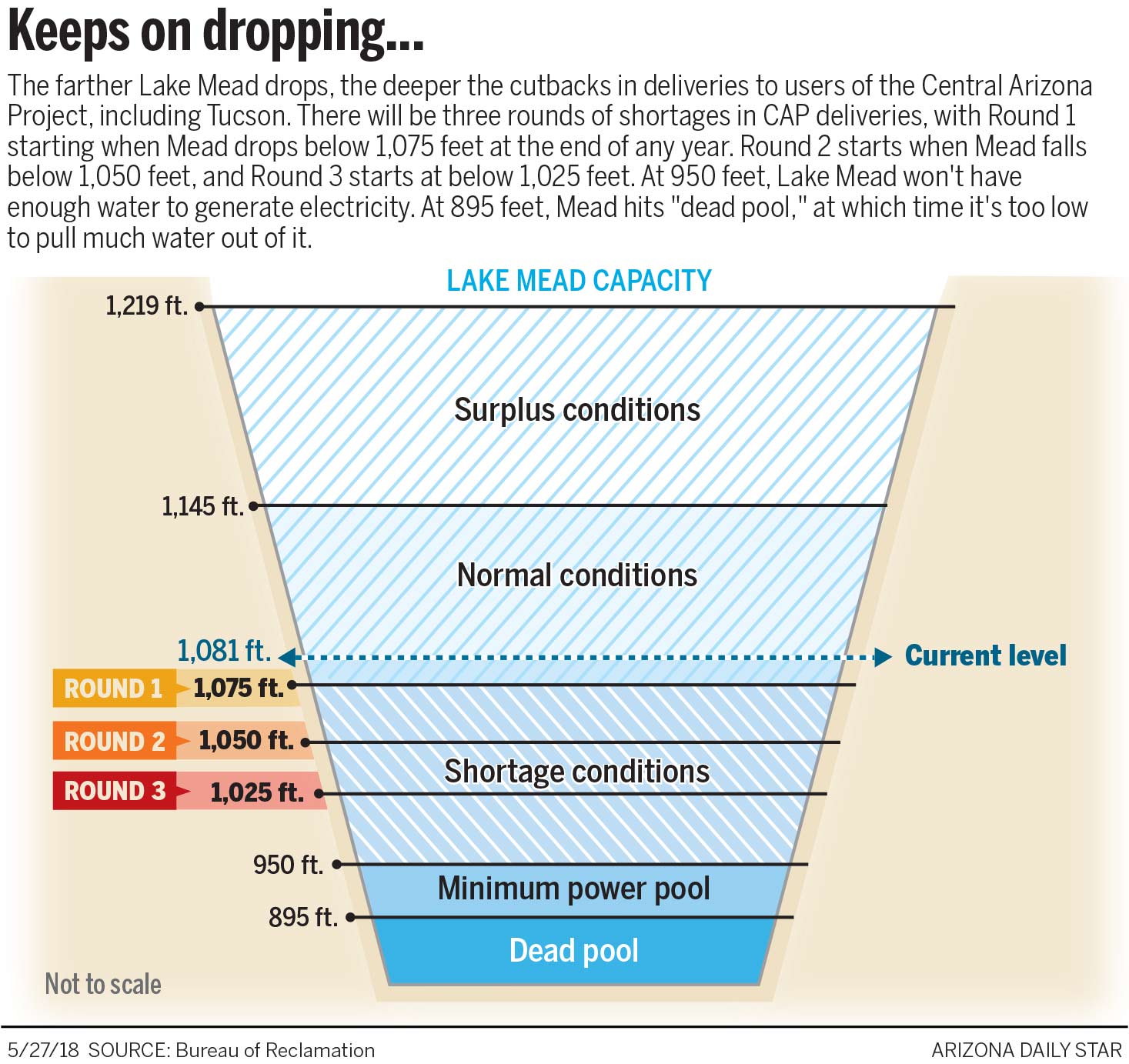

If the region gets nine consecutive dry years like 2001 to 2008, without approval of a drought plan, “there is a possible and plausible scenario” in which Lake Mead on the Colorado drops below 1,000 feet by 2022 and 975 feet by 2025, said Fulp.

At 1,000 feet, Lake Mead would hold half the water it normally delivers each year to the Lower Basin, Fulp said. That could trigger major cuts to cities such as Tucson and Phoenix.

“I don’t want to leave you thinking that the sky is falling. But if we’re in that scenario, the sky is falling,” said Fulp, director of the bureau’s Lower Colorado Regional Office.

While water users can control how much water they conserve, “the thing that would keep me up at night, and does sometimes, is what are we going to do if this drought doesn’t turn around?” he said.

Burman touted the drought plan as a way “to buy down this risk, to invest, to create insurance policies if you will.”

Citing the storied history of officials who built the river’s dams and canals —Hoover Dam, the California Aqueduct, the CAP and Glen Canyon Dam — she implored:

“It’s time for us to look at ourselves and say what are we doing, so people 10 years from now, 20 years from now, 40 years from now, so the people who will depend on the water we are using now can use it.”

2. CAP officials are concerned that conserving “too much” water in Lake Mead could trigger a premature shortage in water deliveries first for Arizona farms, and later for Phoenix and Tucson’s drinking water. Others say that isn’t valid.

The Central Arizona Project’s concern stems from federal guidelines for managing the Colorado River, which seek to balance levels in Lakes Powell and Mead.

The guidelines call for Powell to ship more water to Mead if the latter reservoir is too low and less if it’s seen as too high. So, if too much water is conserved in Mead, the source of CAP’s water, a CAP shortage would be more likely because Lake Powell would send Mead a lot less water than otherwise, the project’s officials say.

That position triggered last month’s blast of letters from four Upper Basin states and water utilities for Denver and Pueblo, Colorado, accusing CAP of “gaming” the reservoir system, charges CAP heatedly denied.

That issue aside, the Arizona Department of Water Resources says CAP’s fear is overblown. The amount of water it wants conserved could raise the lake three feet, at most. That won’t be enough to push the lake high enough to trigger a lesser release from Powell, the bureau’s Fulp and ADWR Director Tom Buschatzke agree.

“We would have to conserve massive amounts to get anywhere near a high enough elevation at Mead that might trigger what CAP is concerned about,” Buschatzke said. CAP declined to respond, saying this issue is best discussed in private talks with ADWR.

3. Without a drought plan, the bad tidings that many fear will befall Lake Mead in the distant future could arrive much sooner.

The first fear is that without a drought plan, Southern California’s Metropolitan Water District — the Met, which serves Los Angeles — would soon pull from Mead a lot of water it could leave there otherwise. That by itself could plunge the river into a shortage.

The Met is storing this water in Mead under a program that allows it to remove the water whenever it wants, even if there’s a shortage, as long as there’s a drought plan in place. But if there’s no drought plan, California would not be able to take the water once a shortage happens. That could put pressure on it to take the water out as soon as possible.

Overall, the failure of a drought plan could set the stage for the secretary of the interior to step in and impose drastic cuts in water deliveries to cities and tribes, Buschatzke said. The drought plan would let Arizona decide its own fate, he says.

4. The drought’s additional threat to Lake Powell could threaten Western power production as well as Lake Mead, which supplies water to Arizona.

This year’s well-below-normal runoff into Powell and other issues will lower the lake’s elevation 32 feet this year, federal forecasts say.

Two more bad years and Lake Powell could be approaching 3,525 feet. At that level, Glen Canyon Dam’s power production — mostly for rural areas all over the West, including Arizona — becomes jeopardized as water pressure declines.

The power production would be cut off entirely at 3,490 feet.

Also, Lake Powell at those levels will have less water to send to Lake Mead, dropping Mead still lower.

5. Arizona’s water agencies are making nice now, and a top CAP official sounds almost contrite. But approval of a drought plan remains uncertain.

CAP general manager Ted Cooke sounded conciliatory in a recent speech in Phoenix.

While Arizona has accomplished a lot on water over the past century, leaders are “perilously close” to not meeting their current challenges, said Cooke, and he accepted some responsibility.

“I believe leadership begins with me. While I believe that I do everything I possibly can, and I’m sure every single one of my colleagues feels the same way, we have fallen short and things aren’t working as they need to be,” Cooke told the annual Arizona Water Association conference.

To get the drought plan moving again, CAP and ADWR must resolve key sticking points.

One is whether Lake Mead or suburban developments near Tucson and Phoenix will get Colorado River water that cities and farms have a right to but don’t take each year.

Another issue is how to ease the drought plan’s impacts on Pinal County farmers, who lose their whole CAP supply once shortages occur as the plan is proposed.

Yet another is an apparent political power struggle between agencies about whether the Gila River Indian Community in Pinal County may legally conserve some of its huge CAP supply — twice as much as Tucson’s share — in Lake Mead.

California is another hurdle. The Imperial Irrigation District there must sign on to the plan for it to work.

But first, Imperial officials want a firm commitment backed by hard cash from California and the federal government to keep the disappearing Salton Sea from dropping too low after Imperial farmers cut their water use, which in turn will cut the runoff into the sea. Second, it’s uncertain legally how strictly the district can force its farmers to conserve water.

Once all that’s worked out, Congress must approve legislation to adopt the drought plan.

6. The drought plan is only a band-aid, but putting an end to the fighting is considered essential.

“It is not a long-term solution for the river,” said Patricia Mulroy, former director of the Southern Nevada Water Authority, who helped shepherd many of the river’s 2007 guidelines into existence. “It is a survival tool to give us time to find longer-term solutions,” she said in a Phoenix speech this month.

More work will be needed because the feds have warned that future climate change will reduce river flows enough to create a 3 million acre-foot gap between water use and supply — more than double the river’s current deficit.

But if everyone is sitting in separate corners, primed for a fight, “We certainly don’t have the time, bandwidth and political will to do it,” Mulroy said.

“The lawyers will love us for putting their grandchildren through school. But I don’t think our constituents will.”

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.