Kartchner's cave formations harbor communities of thousands of previously undiscovered bacteria.

Kartchner's cave formations harbor communities of thousands of previously undiscovered bacteria.It all began with a coat of slime.

Along the tour route within the cool, dark walls of Kartchner Caverns, on panels painted to look like rocks—designed to hide hose bibs and other less-attractive details of maintaining a cave—a slick invader had set up shop.

Soapy water, bleach—no matter what the state park’s staff tried, the sticky film kept coming back.

Rick Toomey, then Kartchner's cave resources manager, feared the slime would spread. He took his concerns to University of Arizona microbiologist Raina Maier, who had volunteered to help the cave’s staff after hearing a talk about the site.

Maier put graduate student Luisa Ikner on the case, and Ikner soon made an unexpected discovery: the slime wasn’t an invader at all.

It was a bacterial community native to the cave, happily feeding on the panels’ acrylic paint. The cave’s keepers then did away with the panels and solved their slime problem.

But one question lingered: what else lives in the cave?

The Kartchner Caverns Microbial Observatory project has spent the past five years trying to answer that question. Armed with cutting-edge lab techniques and a cohort of willing students, Maier and her UA colleagues have catalogued the cave’s denizens and what they do, finding a few more surprises along the way.

One of Maier’s willing students is graduate student Marianyoly Ortiz, known in the lab as Marian. Since arriving on campus four years ago, she has taken up Ikner’s mantle and helped keep the Kartchner project alive.

University of Arizona graduate student Marianyoly Ortiz is one of very few researchers keeping Kartchner-based microbial studies alive.

University of Arizona graduate student Marianyoly Ortiz is one of very few researchers keeping Kartchner-based microbial studies alive.A native of Puerto Rico, Ortiz grew up on a farm in a small mountain town, “surrounded by cows and chickens,” she says. Her mother, a nurse, emphasized and encouraged her children’s education, and studious, soft-spoken Ortiz made her way through school intending to become a physician.

It wasn’t until a university biology class that she fell in love with bacteria.

“They are everywhere, and they have so many responsibilities,” she says. “They are involved in every process on this earth.”

When she landed in Maier’s lab and got hooked on Kartchner’s microbial communities, Ortiz found herself closer to those processes than she ever expected.

To obtain samples of the cavern’s bacteria, Ortiz must be escorted to sections of the cave that are closed to the public; she must climb up and down steep passages and stand for hours in sticky mud, running scores of sterile cotton swabs along the walls, one by one, and storing them in tubes of de-ionized water without contaminating them, before emerging again with tubes intact.

For Ortiz, who calls herself “not a sports person,” the journey is a challenge and an adventure.

Park Ranger Ginger Nolan, who has served Kartchner Caverns for 14 years, is the gatekeeper of the adventure. She leads Ortiz and the handful of other researchers working on the cave where they need to go.

“You take a lab worker down a 30-foot wall, and then try to climb them up a 30-foot wall, and it’s pretty comical,” she muses. “But they get stronger and better every time, and watching their eyes light up—it’s a good feeling.”

Once back in the lab, another kind of adventure unfolds. Ortiz must extract DNA from the tiny sampling of bacteria on her swabs. Each swab can contain DNA from many different bacteria, so she focuses on a single gene.

Called 16SrRNA, it is found in all bacteria, but varies slightly from one bacterial group to another. The differences allow Ortiz to identify the different groups present in the sample.

Ortiz amplifies the DNA fragments and picks out the patterns in each specific version of 16SrRNA she finds in the sample. She then compares the sample’s gene sequences with those in databases of bacteria already known and studied in other labs. Many of Kartchner's denizens don't match anything seen before.

So who are these mystery microbes?

Ortiz, Maier and the other researchers working on Kartchner’s bacterial communities have a few answers so far.

They know Kartchner’s microbes have to be hardy and unusual to survive in a world with no sunlight and scant nutrients. About 2,000 species make their home in the cavern—a high number given the hostile setting—and they’re a remarkably diverse lot.

“Compare one stalactite to another stalactite just two feet away, and they have different microbial communities,” says Ortiz. “A different room in the cave will have a completely different community.”

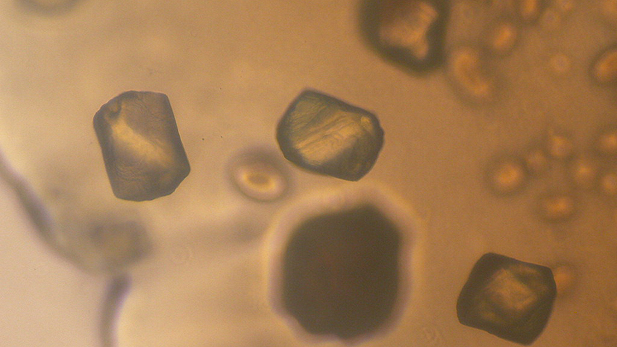

When spared the DNA extraction and allowed to grow in the lab, some of the bacteria produce their own bright red pigment. Others appear to grow crystals of calcium carbonate, the same material the cave’s formations are made of. And some may yield the medical and environmental solutions of the future.

Humans have tapped bacteria for everything from medical applications to oil spill cleanups, says Maier, and the genetic codes of Kartchner’s microbes hint that they too might have such helpful functions.

“We think there may be genes and functions there that we can harness for society,” she says.

But it isn’t yet clear which antibacterial, antifungal or other useful properties the microbes wield.

In Maier’s lab, as in all others, the answers inevitably lead to more questions. No one knows whether the microbes rely primarily on the cave’s meager organic material or on minerals for energy, or how big a role their crystal-making abilities play in the development of cave formations. Finding out could point researchers to new products, as well as better ways to care for the cave.

The search goes on, and its funding will run out in a year. Nevertheless, Ortiz, Maier and the rest of the Kartchner converts remain hopeful.

“I am worried about it, but it will be what it is,” says Maier. “I’m sure we will find a way to keep our work in the cave going. Something good will come from it.”

Researchers hope the bacterial communities' hidden abilities--including the ability to produce their own crystals in the lab--will prove useful to society and helpful in managing the cave.

Researchers hope the bacterial communities' hidden abilities--including the ability to produce their own crystals in the lab--will prove useful to society and helpful in managing the cave.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.