The main entrance to Banner University Medical Center.

The main entrance to Banner University Medical Center.

Nationwide clashes between Border Patrol and health care providers may be putting the health of migrant patients at risk.

Kathryn Hampton, a researcher for the nonprofit Physicians for Human Rights, says medical providers all over the country are clashing with federal immigration agents over the care of migrants when Border Patrol agents transport immigrants to health care facilities.

Last week, the group released a report called "Not in My Examining Room."

"Immigrant patients, their privacy protections, are really being eroded in a way that could really be dangerous for their health," said Hampton. "Customs and Border Protection personnel have a lot of discretionary authority. And sometimes they are exceeding the limits of their mandate," she said

Estrella Madrigal, 23, says after her husband was murdered in Honduras, she was alone and vulnerable. She talks about being repeatedly raped in Honduras by the gang that killed her husband. In desperation, she decided it was better to risk dying in an effort to get to the U.S. than staying in the life she was living in Honduras. She left with her 5-year-old son and 15-year-old sister.

When she arrived at the Nogales port of entry, she says she felt like she was just barely hanging on to life. She claims when transported to a Tucson hospital, a Tucson Sector Border Patrol agent handcuffed her to the bed and never allowed her to talk to the doctor in private.

"I just kept my mouth shut," she said, never telling the doctor the emotional and physical trauma she had endured in Honduras.

VIEW LARGER Doctors and medical professionals demonstrating in Washington D.C. to advocate for migrant rights (May 2018).

VIEW LARGER Doctors and medical professionals demonstrating in Washington D.C. to advocate for migrant rights (May 2018). The Tucson Sector Border Patrol would not comment on the topic, and instead referred questions to federal officials in Washington, D.C. Border Patrol is a unit of Customs and Border Protection, which responded by referring to a 2015 Customs and Border Protection manual on transport, detention and search standards. The manual does not address the question of who has final authority when it comes to immigrant health care decisions while in a medical facility — the agent or the doctor or the patient.

A group of men, women and children prepare their documents after approaching and surrendering to Border Patrol in the Yuma Sector, 2019.

A group of men, women and children prepare their documents after approaching and surrendering to Border Patrol in the Yuma Sector, 2019.

Another Tucson case that has garnered national publicity is that of a 20-year-old pregnant woman from Guatemala. The young woman was rushed to Banner-UMC by Border Patrol. The woman was dehydrated, exhausted and showing signs of going into premature labor. Fourth-year medical student Rom Rahimian was treating her.

"My biggest concern was really her safety and well-being, and the safety and well-being of her unborn child," he said

Rahimian and other medical staff were able to stabilize her, recommended she needed more time to recover. Instead, said Rahimian, the Border Patrol agent assigned to the young woman was pressuring him to release her. Rahimian says hospital staff didn't know where the officer's authority ended and theirs began.

"What can we do? What are the rights? Is there anywhere else we can send this patient? We called the Guatemalan Consulate. Finally, I'm so grateful that the Florence Project got back to me and said, 'Hey Casa Alitas, this group they will help you.'"

And the staff at Casa Alitas, which is part of Catholic Community Services, did help. The group also runs the Benedictine Monastery for migrants in midtown Tucson. The woman was sent there instead of a holding cell.

This scenario is playing out between immigration officials and hospital staff all over the country, says Hampton of Physicians for Human Rights. Where does the authority lie to make the decisions for migrant medical care?

"[That] question really gets to the heart of this issue. And what Physicians for Human Rights strongly advocates is that health care providers need to be the ones making those medical decisions," said Hampton.

Last week, leaders from Customs and Border Protection's Tucson Sector met with officials from Banner-UMC to discuss the issue.

Banner-UMC wouldn't disclose the specifics of the meeting, but sent AZPM a statement which reads, in part: "We requested that Border Patrol provide reasonable privacy for patients [in their custody] during the course of medical care and/or medical discussion, unless a patient is considered a threat to himself/herself or our hospital staff."

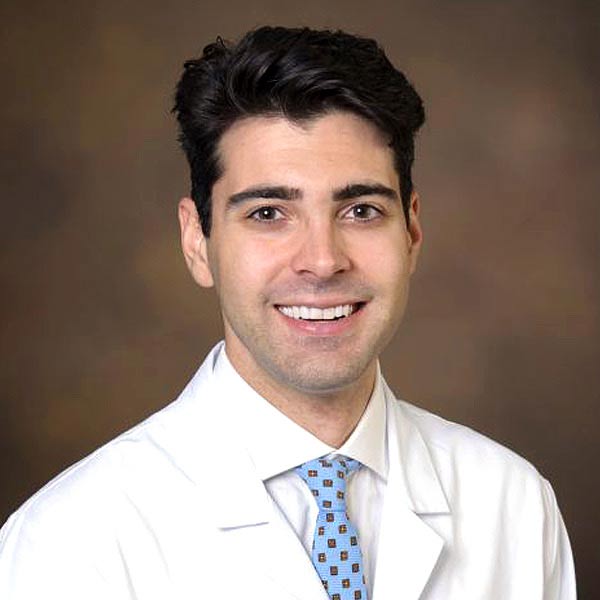

VIEW LARGER Rom Rahimian is in medical school student at the University of Arizona. (2019)

VIEW LARGER Rom Rahimian is in medical school student at the University of Arizona. (2019) In the meantime, Rahimian, the UA medical student, says he will continue to do what he feels is best for his patient whether they are a U.S. citizen or not.

"I think it is important to maintain the dignity and humanity of these people."

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.