A collected sample undergoes coronavirus testing.

A collected sample undergoes coronavirus testing.

Vanessa Gallego spent the better part of last week trying get her uncle’s family tested for COVID-19.

"They said, 'Vanessa please, find someone who can do this immediately', because I’m hearing that through AHCCCS and El Rio, they’re looking at 10-15 days to find out," she said.

She said her uncle called in a panic after the family was exposed to someone with the virus. They wanted answers as soon as possible and most places were backed up for days. That’s why she was contacting a specific clinic that promised results within thirty minutes. But it came at a cost.

"[The test is] $125 per person. And this is a family of four. So you can do the math and see how expensive this would be for a family to test for one moment in time," she said.

Gallego is a Southside business owner and an organizer with Families United Gaining Mobility. The organization addresses access issues in predominantly Latino neighborhoods in Tucson’s south and west sides. She said families in those areas face challenges made worse by the pandemic. Immigration status can block people from accessing healthcare. Plus, fear of running into immigration or Border Patrol agents may prevent people from getting tested at all.

"If there is support on the Southside, it’s not enough. Because historically, we’ve seen that, whatever resources we have, it’s still not enough," she said.

Those aren’t just problems in Tucson. Data released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention last week show glaring COVID-19 disparities nationwide. Black, Indigenous and Latino Americans are affected at rates far higher than their white neighbors. Using that data, the New York Times analyzed over half a million cases and found Black and Latino Americans are three times as likely to contract the coronavirus and almost twice as likely to die from COVID-19. The data isn’t complete, but so far Latino communities show the highest rate of infections per 10,000 people nationwide. That trend is mirrored in Arizona.

"There are vulnerable populations and we want to make sure they have access to care," said Pima County Health Department Director Dr. Theresa Cullen.

Thirty percent of the county’s COVID-19 cases are Latino. That’s the largest percentage of known cases. Dr. Cullen said some forty percent of cases don’t have demographic data because the county wasn't collecting that information until the first week of May. She said the data they do have is in part reflective of the demographic makeup of the county, but it also shows disparities.

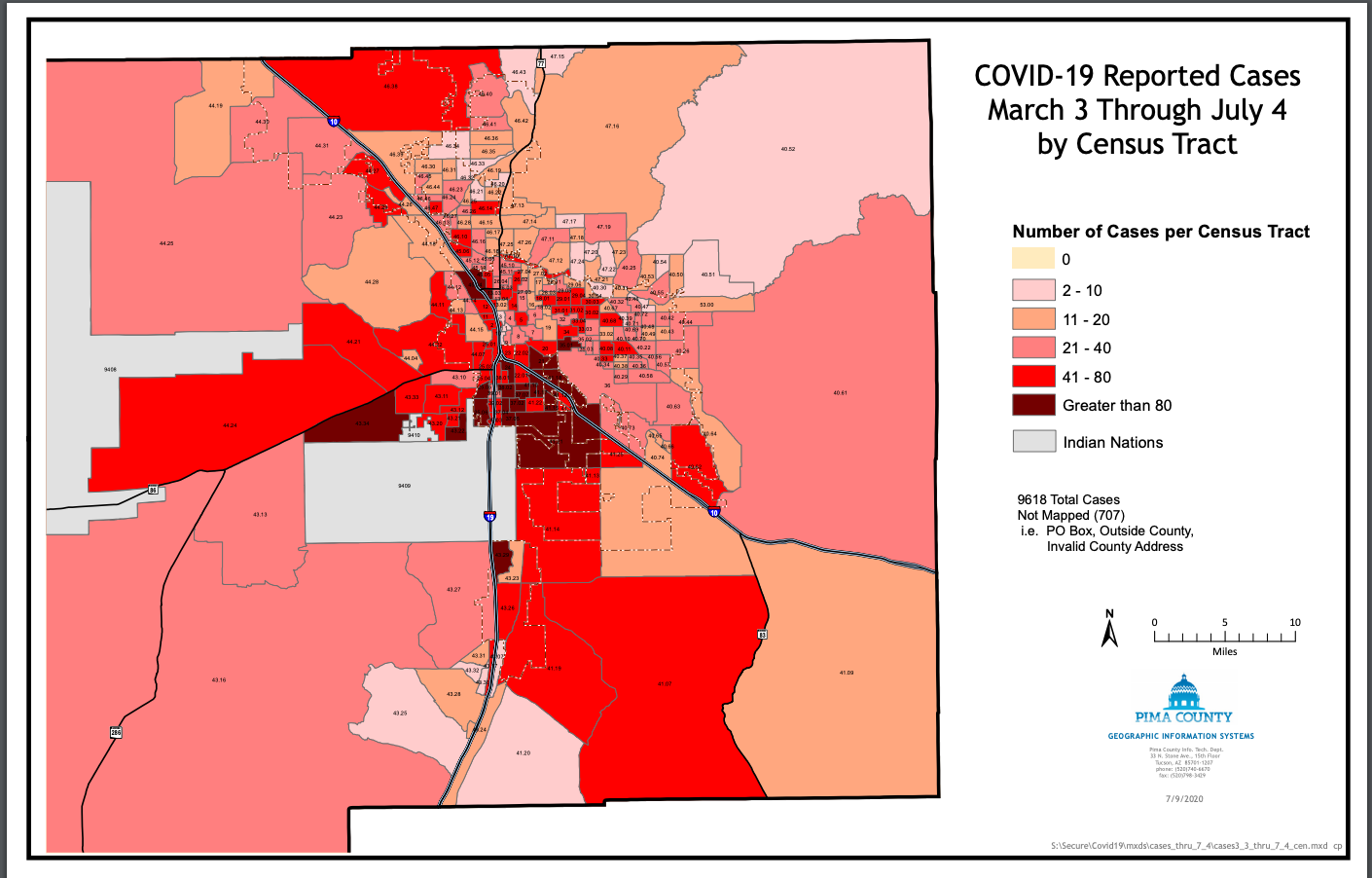

"When we do some GIS mapping, by census track and zip code, we do have some areas that seem to have a higher rate of cases," she said.

VIEW LARGER Data gathered by the Pima County Health Department show concentrations of cases, in some cases more that 80 per census tract, in neighborhoods in Tucson's south and west sides as well as the city of South Tucson.

VIEW LARGER Data gathered by the Pima County Health Department show concentrations of cases, in some cases more that 80 per census tract, in neighborhoods in Tucson's south and west sides as well as the city of South Tucson. Data provided by the county shows concentrations of cases in Tucson’s southside and westside and the city of South Tucson, with some neighborhoods showing concentrations of more than 80 cases per census tract. The health department is starting to offer free tests by appointment at two sites to serve those areas. The first, which launched Monday at the Kino Event Center, booked a full week of appointments by Friday of last week.

Still, activists point out Latino risk factors go beyond access to testing. César Fierros, who works with community organization LUCHA AZ, pointed out that many Latino people work essential jobs in hospitals, grocery stores and janitorial services and can’t stay home.

"Just by the nature of the job that you have you’re putting yourself at great risk, and I think that’s one of the big factors that leads to a big increase in cases and also mortality rates," he said.

He said many Latino households are multigenerational. That makes it hard to quarantine at home and increases the chance of spreading the virus. Fierro said the state failed to protect Arizonans when it mattered most.

"If we’re forcing people back to work then we should do everything we possibly can to take care of people," she said. "And unfortunately our governor has failed to provide that relief."

That concern is echoed by Claudia Jasso, who leads a Latino health advocacy group in Tucson called Amistades. She said even in normal times, many of the families her organization workers with face challenges with food security and access to healthcare. That's why during the pandemic, the group has helped families with cash assistance for essentials. She said even though many families are afraid of contracting the virus, they still have to go to work.

"They are essential workers, most of them are essential workers," she said. "So they don’t have the luxury of saying, I’m afraid to go back to work. It’s a life or death decision and they have to make it because they have no other way."

Jasso said Amistades is looking for health partners in Pima County to provide ramped up testing and COVID-19 care to the families they serve.

Dr. Cullen said the county is ramping up contact tracing efforts and trying to improve testing access. But Southside business owner Vanessa Gallego said there's still a long road ahead in addressing the virus in her community. And she said a recent story about a problematic testing site in the area undermines community trust. At the beginning of this month, people reported waiting in long lines to be tested at an urgent care clinic on the Southside, only to later learn a lab error made their tests invalid.

"Leaving your home, going to places like that, you're exposing yourself and raising your risk of exposure, so to find out they did the test wrong hurts the community's trust is systems like this," she said. "Did it happen anywhere else in town? Did it happen on the east side or the north side? No it happened on the Southside."

In the end, Gallego was able to get her uncle’s family a testing appointment at a Southside location offering rapid tests. She said going forward, she'll keep listening to community members and trying to find answers.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.