John Farley, director of fire test operations at the Naval Research Laboratory, tests the effectiveness of aqueous film-forming foam by spraying it on a gasoline fire. The test took place at the laboratory in Chesapeake Beach, Md. Oct. 25, 2019.

John Farley, director of fire test operations at the Naval Research Laboratory, tests the effectiveness of aqueous film-forming foam by spraying it on a gasoline fire. The test took place at the laboratory in Chesapeake Beach, Md. Oct. 25, 2019.

The Buzz for September 30, 2022

The issue of water contaminated by per- and polyfluoroalkyl chemicals, also known as PFAS or forever chemicals, has been on the mind of the public and policymakers.

Most notably, the chemicals are showing up in aquifers around the state.

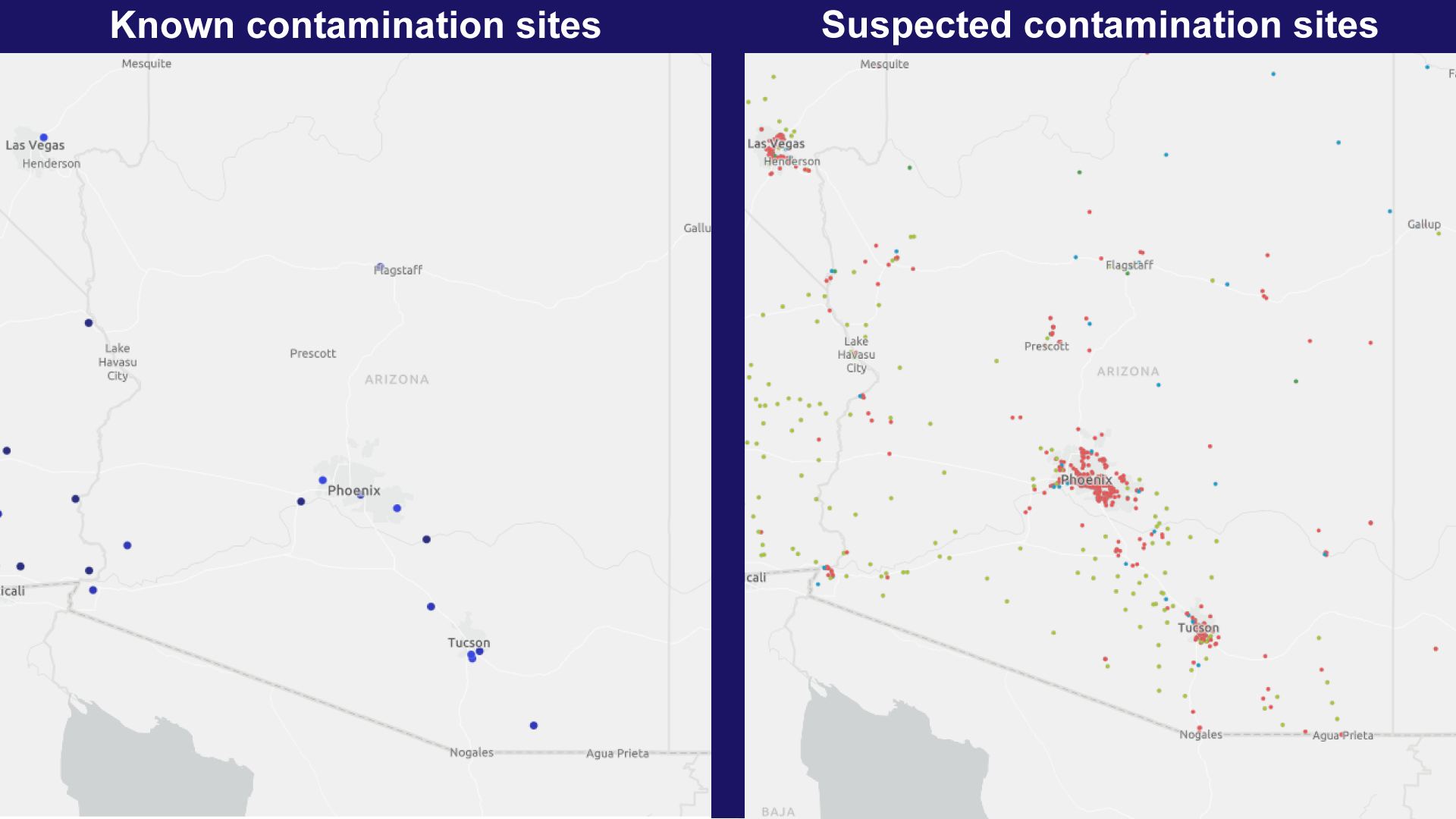

A map of known contamination sites put together by the PFAS Project Lab shows 13 sites in Arizona. The map does not include six wells that recently tested positive in the Prescott area.

The project also notes that there are many more sites where they suspect PFAS contamination.

"We know a lot about a very small number of chemicals in [the PFAS class]," said Alissa Cordner, Co-Director of the PFAS Project Lab. "A few dozen."

Estimates say there could be as many as 12,000 chemicals in the class, but Cordner said they all have similar chemistries.

"They're bio-accumulative, they can accumulate in the body. They are persistent, so they don't break down in the body. And they are toxic to many different organ systems ranging from our liver system to our immune function to various aspects of reproduction and the development of a healthy fetus and a healthy baby."

And health effects begin at low levels of exposure.

"The US EPA just updated their health advisory levels for two of the most widely studied PFAS," said Cordner. "And the EPA calls them near-zero levels. They are below one part per trillion."

Cordner called PFAS ubiquitous in our world because they are useful. They easily spread into thin layers and are able to repel water and grease. They can be found in everything from non-stick cookware to food packaging and some water-repellent outdoor gear.

"They are also contaminating drinking water around the country and around the world, both through industrial sources of contamination, for example, a chemical company that uses PFAS," she said. "They're also widely used in certain types of firefighting foams, specifically foams that are used to fight high-intensity oil and gas fires."

That is much of how PFAS have found their way into Arizona's aquifers. All of the sites where contamination has been found in Arizona are associated with military bases or airports.

When it comes to minimizing exposure, Cordner said that PFAS' ubiquity can make them hard to avoid.

"The best thing we can do is to encourage policymakers and decision-makers to regulate these chemicals more efficiently, to turn off the tap of new production and emissions to reduce our overall exposure."

Local policymakers have begun such work at one PFAS site in Tucson, where, like many places, the aquifer near military installations has been contaminated with PFAS.

Wells near Tucson International Airport, which houses the 162nd wing of the Air National Guard and Davis Monthan Air Force Base have tested positive, and Tucson Water is leading an effort to remove the chemicals.

Tucson Water Director John Kmiec explained how at one such site, which sits on a nearly half-acre lot in a residential area just north of David Monthan, works.

The Central Tucson Groundwater Treatment System, located near Davis Monthan Air Force Base, removes PFAS contaminates from the aquifer below the area.

The Central Tucson Groundwater Treatment System, located near Davis Monthan Air Force Base, removes PFAS contaminates from the aquifer below the area.

“The vessels are filled with a media, almost like little ball bearings, and that media is specifically designed to hold and absorb PFAS compounds. So it’s doing that and then the water coming out the end is essentially PFAS free.”

The facility treats about 200,00-300,000 gallons of water a day, according to Kmiec. The vessels that it flows through and the medium that pulls PFAS out of the water are monitored by the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality.

"When [ADEQ] knows it's fully absorbed, they'll make arrangements for the medium to be removed from the vessels and delivered to a hazardous waste facility where it's incinerated at a high temperature, which destroys the PFAS compounds."

Kmiec said he thinks this site will run indefinitely, in part because it is a pilot project, but also because it is working.

"What it's doing is providing data on the effectiveness of the media. So if and when we build other treatment plants in this area, we'll have it dialed in."

Kmiec said that if this project proves successful, treatment centers like this site could dot the area around the contaminated aquifer someday.

The pilot project in Tucson is a collaboration between the city and the state, with money coming from the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality. But actions to remedy the problem that PFAS have created are happening up to the federal level.

The recent Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act included $13.5 million in federal funds for PFAS remediation in Arizona.

And that is only a small portion of what is available, according to Melanie Benesh, Vice President of Governmental Affairs for the Environmental Working Group.

“There is at the moment a lot of money available for this," she said. "There was $10 billion included in the bi-partisan infrastructure deal that passed in the fall, specifically for emerging contaminants. So that would include PFAS and other sorts of under-regulated chemicals.”

Benesh said that the Environmental Protection Agency has begun instituting laws and regulations around PFAS, but state governments are proving to be more proactive.

"We now have several states that have their own drinking water standards, that have clean-up standards for PFAS in groundwater and soils. Several states have taken steps to ban certain uses of PFAS like in food packaging and cosmetics. None of those things have happened on the federal level yet."

The federal government has made one move that will prove particularly beneficial, she said. Especially when it comes to what has caused PFAS contamination of Arizona's groundwater.

"At the end of 2019, Congress banned the use of PFAS in firefighting foam beginning in, I believe, October of 2024. So the military has a deadline to figure out which kind of firefighting foam they're going to use to replace the firefighting foam that has PFAS. There are alternatives that are available and have been on the market for some time. But the [Department of Defense] has a firm deadline for when they need to make that switch."

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.