This year marks the 53rd annual Tucson Juneteenth Festival, where community members come together to celebrate the emancipation of enslaved people. But what many Tucsonans do not know is that Tucson’s connection to the jubilee dates back to the late 1800s.

Arizona Historical Society Archivist Perri Pyle began her research into Tucson’s history after learning of the stereotype that there were not enough Black people in Tucson for there to be a Juneteenth then.

“I was like there’s just no way that’s accurate,” Pyle said. “So I decided to do some digging and see as far back as I could possibly find in Tucson newspapers.”

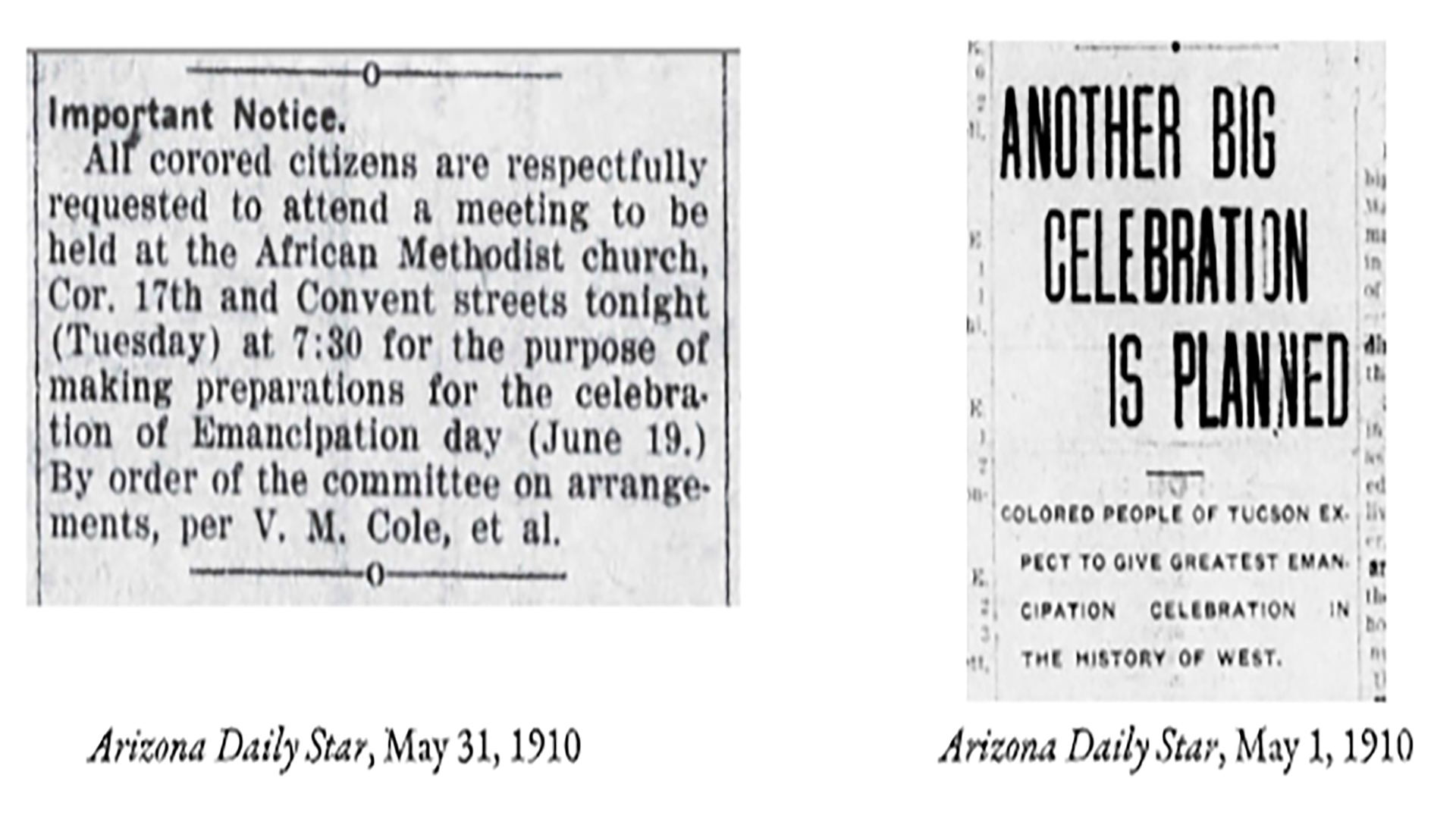

Pyle sifted through Arizona Daily Star Archives to find keywords like June 19th, “freedom day,” “jubilee day” and even “emancipation day.”

“There was one article I found in the Daily Star from June 14 1904 that said, ‘there is some talk of the colored people of Tucson celebrating on the 19th day of this month, that day is the anniversary of their freedom,’” Pyle recited.

The Great Migration was one of the largest movements of people in U.S. history. At the time, nearly six million Black people were leaving the South to states across the nation. As communities moved, they brought their traditions with them as well.

“A lot of the black community, in early times, like pre-state times in Arizona, did come from Texas,” Pyle said. “A lot of people were moving West to try to seek better opportunities…and between 1900-1910, the African American population in Tucson grew from 88 to 220.”

The Juneteenth holiday started in Texas but became more formalized in Tucson as more Black families came. But, in the middle of the 20th century, celebrations slowed down.

“The Great Depression really puts a hamper on big formal gatherings, the world wars, and even later, like the Korean and the Vietnam War,” she said. “It seems like there is a movement away from big, grandiose celebrations as people get more frugal, and they're more focused on just daily survival.”

As time went on, celebrations nearly ceased.

These are two excerpts from the archives of the Arizona Daily Star that archivist Perri Pyle used in her research to learn more about Tucson's history with Juneteenth.

These are two excerpts from the archives of the Arizona Daily Star that archivist Perri Pyle used in her research to learn more about Tucson's history with Juneteenth.

Until lifelong Tucsonans like Jack Anderson brought the tradition back in the late 60s. His family, like many at the time, moved to Tucson in the early 1940s from East Texas. Before Juneteenth became what it is now, Anderson said his family celebrated what they called Big Sunday, an extension of Juneteenth.

Eventually, Anderson and his friends saw a need to bring the community together, especially during a time of uncertainty following the civil rights movement.

“We were the vanguard, as we like to say,” Anderson said. “We're the ones that took out the chances. We took the harassment because believe me the local city establishment wasn't happy about Juneteenth.”

Anderson recalls the first celebration as only a thought that started underneath a tree in the Vista Del Pueblo park with his friends.

“Everybody did their thing and brought it all back together. That's what I remember the most, I remember the teamwork. I remember the love, definitely unity.”

He saw and still sees the celebration as a form of resistance to racial injustice, which is not an uncommon belief when understanding Juneteenth’s influence. Pyle found an article written by JC Clemens, an early leader in Tucson’s Black community, that shared similar ideas.

“I found an article early on from the 1910 Tucson Juneteenth Celebration in which JC Clemens stated that his organization was going to be celebrating Juneteenth in order to keep them on the front ranks of progress,” Pyle said.

When there was no space, Tucson’s Black community made it. Decades later, the tradition continues and grows bigger by the year.

As Anderson looks back on his time in Southern Arizona, he will always remember Juneteenth as the platform that gave him the ability to showcase his life’s work–music– at a time when Black musicians were not always seen.

“If it hadn’t been for that, who knows? It gave me an opportunity to play my music, learn the music and get involved in a dream.”

Now, Tucsonan Larry Starks heads the annual festival, taking after his brother, Burney, who was a longtime advocate for the holiday to be recognized both in the state and nation. He sees it as a greater cause.

“It's not just a racial justice movement; it’s an inclusivity movement, saying that we're the best that we can be no matter what I look like, no matter what you look like, no matter what my beliefs are, no matter your beliefs, we could come together and still appreciate each other.”

Starks hopes to continue the work that others like his brother and Anderson have done by expanding the celebration across the state.

“I'm shooting to make Juneteenth the biggest celebration in Southern Arizona,” Starks said. “When I look at their shoes, and what they started I think this is how we elevate that. This is how we keep it going. This is how we bring the young people in and this is how we create legacies.”

And if there is no space or an idea has not been done before, Anderson says do not let that stop you from making change.

“If you don't have it, make it, build it, you can do it. Young people, you can do it. Old people, you can do it. Sometimes it just starts with one.”

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.