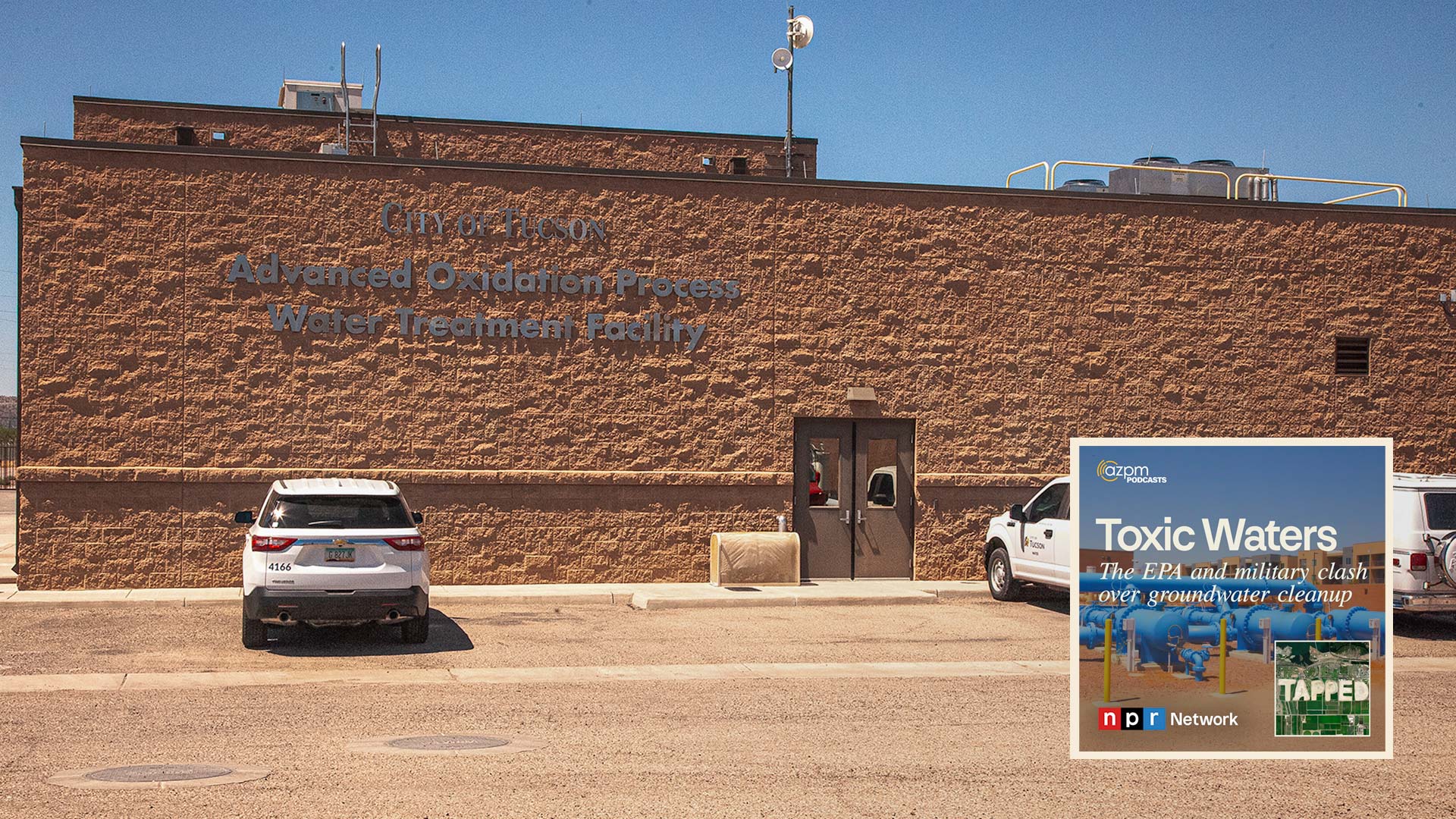

Tucson Water's Advanced Oxidation Process Treatment Facility located at 1110 W. Irvington Road Tucson, Ariz. This facility that is operated and maintained by Tucson Water was brought online in 2014, and works in conjunction with the adjacent Tucson Airport Remediation Project (TARP) to treat for trichloroethylene known as TCE, 1,4 dioxane and other volatile organic compounds.

Tucson Water's Advanced Oxidation Process Treatment Facility located at 1110 W. Irvington Road Tucson, Ariz. This facility that is operated and maintained by Tucson Water was brought online in 2014, and works in conjunction with the adjacent Tucson Airport Remediation Project (TARP) to treat for trichloroethylene known as TCE, 1,4 dioxane and other volatile organic compounds.

Tapped: Season 3 Episode 03

A Tucson mother's loss turned into a national movement to make drinking water safe. Forever chemicals, including PFAS, are tied to cancer and other health problems. Now the race is on to clean up Tucson's water and protect public health.

More from Tapped

KM: In May, the Environmental Protection Agency issued an administrative emergency order under the Safe Drinking Water Act to the U-S Air Force and Arizona Air National Guard regarding the Tucson International Airport Superfund Site.

KM: The site, which makes up about ten square miles beneath the Tucson International Airport, the Morris National Air Guard base, and what is known as Air Force Plant 44, contains groundwater contaminated with volatile organic compounds including trichloroethylene known as TCE, 1,4 dioxane and PFAS.

KM: The order calls on the Air Force and Air National Guard to abate the threat to health presented by per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances known as PFAS, at the site.

KM: This month, the U-S Air Force served EPA, asserting that the agency should drop its order for lack of threat to human health and the impossible nature of the request.

ZZ: So who’s responsible here? Have the Air Force and other polluters done enough to clean up forever chemicals? And, how long will it be before the water under this part of Tucson is safe to drink again?

ZZ: This is Tapped, a podcast about water. I’m Zac Ziegler.

KM: And I’m Katya Mendoza.

Arizona's water supply continues to dwindle. So, how do you take water that we made too dangerous to drink decades ago and get it back to where we can safely use it?

LS: In 2019, my husband Oscar was diagnosed with prostate cancer and had to undergo cancer treatment and healthcare monitoring.

KM: That’s Linda Shosie. She’s a long-time resident of Tucson's south side.

LS: So Tiana was diagnosed with lupus and kidney nephrotic syndrome in 2004, and she died in 2007.

KM: Is she your oldest?

LS: No Tiana was my fourth child, I have eight children…My children started as early as the 1970s, my children, my older children were born with birth defects.

LS: The year after Tiana died in 2007, which was 2008, Clarissa my daughter Clara, she was diagnosed with lupus and kidney nephrotic syndrome just like Tiana. She’s currently in her end stages. She’s very young, still.

LS: And then Joseph in 2009, he was diagnosed with male lupus and skin, he would suffer rare skin rashes. Then in 2011, my daughter Paula…which is my child after Jojo, she gave birth to a little baby boy who was born with cleft lip.

KM: Linda’s the founder of Tucson’s Environmental Justice Task Force, a community-led group that organized in 2016, with the purpose of advocating for Tucson residents who have been impacted by PFAS contamination in their water.

LS: When I founded the Environmental Justice Task Force, our primary focus was on another chemical, TCE, that also was released at the Tucson International Airport Superfund Site. In addition to advocating for the cleanup and regulations of TCE, I began to, I began to look into what other chemicals had contaminated our water supplies.

KM: She says that information was hard to come by at the time. But in 2018, Tucson Water detected multiple PFAS chemicals at the Tucson Area Remediation Project facility within miles of her home.

KM: Upon discovery of PFAS chemicals in the TARP wellfield, Tucson Water shut down three wells to reduce the amount of PFAS entering the facility. Currently, five wells remain out of service due to high concentrations of PFAS that cannot be addressed by the existing treatment system.

ZZ: Tucson Water took us on a tour of that facility.

[nat sound walking at the TARP]

ZZ: What is this thing that is kind enough to offer us some shade at this very warm moment?

SS: So this is actually the original TARP facility which was first brought online in 1994.

KM: That’s Scott Schladweiler, deputy director of Tucson Water.

ZZ: A note of disclosure, Tucson Water is a sponsor of this podcast and AZPM, but we treat them like we treat anyone else involved in a story.

SS: But, to take it back a step, the TARP and the Superfund Site that we talked about was really identified in 1983 and put on the National Priorities List in 1983, after identifying high concentrations of TCE, trichloroethylene coming from the airport site

SS: So after several investigations and a number of reports and studies and designed, the TARP facility that you see here which is now offline was created to remove and treat for TCE or trichloroethylene and that water was treated and then put back into the potable distribution system.

KM: Schladweiler is referring to the pack polymerization or air stripping process that is effective in removing TCE but not 1,4 dioxane.

SS: So just looking at the site, this is actually where everything comes into the site. There are two separate wellfields, so we have a total of ten wells that serve this facility. There’s a north well field and a south well field and they come into that site and right now is where they used to go in here they now are directed over to the sediment removal system which is up on the north side of the plant. We can take a walk over there if you’d like…

VIEW LARGER The North Wellfield at the Tucson Advanced Oxidation Process Water Treatment Facility. There are two sets of wells that are located at different depths because of a perched aquifer. Water from those wells located on the underground plume travel into a blending station that combines water from the wellfields before before being fed into the AOP booster pumps.

VIEW LARGER The North Wellfield at the Tucson Advanced Oxidation Process Water Treatment Facility. There are two sets of wells that are located at different depths because of a perched aquifer. Water from those wells located on the underground plume travel into a blending station that combines water from the wellfields before before being fed into the AOP booster pumps. [nat sound walking at the TARP]

KM: Scott says there are a series of ten wells between the TARP and the Tucson International Airport, strategically located in areas where they capture the water.

SS: The two different well fields are located at different depths because there’s a perched aquifer– some of the water is floating across the perched aquifer and some of it’s well beneath it.

KM: Tucson Water installed the Advanced Oxidation Process facility which was brought online in 2014. It treats both.

KM: You’ll hear Scott refer to it as UV AOP; ultraviolet advanced oxidation process.

KM: The AOP facility uses ultraviolet light and hydrogen peroxide to break down 1,4 dioxane, TCE and other volatile organic compounds.

SS: It’ll actually destroy the hydrogen peroxide and destroy that bond between the elements here that breaks it up into inert compounds that are no longer harmful when put together so that’s the purpose of the hydrogen peroxide and then the GAC which we’ll talk about over there later, is put in place to remove any excess hydrogen peroxide that’s left in there, cause we don’t want that going out into the distribution system.

KM: Scott says there's between 72 and 84 UV lamps that water passes through that help break up the compounds.

SS: They do get fouled up over time just like you see at home with hard water or any film that builds up so there are wipers that go back and forth over these to help keep them clean but this is one of the things that requires constant maintenance.

VIEW LARGER Ultraviolet advanced oxidation process reactors inside of the Tucson Water Advanced Oxidation Process Water Treatment Facility. Tucson Water's AOP Water Treatment Facility. Between 72 and 84 bulbs within the vessels, use UV lighting and hydrogen peroxide to create a hydroxyl radical that breaks down contaminants in water that passes through.

VIEW LARGER Ultraviolet advanced oxidation process reactors inside of the Tucson Water Advanced Oxidation Process Water Treatment Facility. Tucson Water's AOP Water Treatment Facility. Between 72 and 84 bulbs within the vessels, use UV lighting and hydrogen peroxide to create a hydroxyl radical that breaks down contaminants in water that passes through. ZZ: I’ve been to the one by the airport, that had, it seemed almost more like it was kind of collecting and filtering out the PFAS, this it sounds like it’s a little more breaking down these components before they go out rather than just pulling it out and figuring out what to do with it later.

SS: Correct, yeah so this actually treats it, it actually destroys the 1,4 dioxane and TCE at a molecular level and it actually breaks that bond apart whereas I think what you’re talking about was the Central Tucson Project, yeah that actually filters it out which is, that’s removing PFAS, that’s not removing any TCE or 1,4 dioxane there, that’s strictly PFAS and that’s similar to what you’re going to see out here with the vessels where they’re full of granular activated carbon, where in the case of PFAS, it actually absorbs to the carbon just like you’re saying and that’s what actually removes it.

KM: In 2014, Tucson Water began treating the groundwater for PFAS using the Granular Activated Carbon system, originally installed to quench excess hydrogen peroxide from the UV AOP.

KM: That's the GAC that you heard Scott talking about earlier.

KM: This final step of the treatment process is to ensure that nothing else reaches the water distribution system before being delivered into the Tucson Water supply.

VIEW LARGER Granular Activated Carbon (GAC) contractors at the Tucson Water AOP Water Treatment Facility. The towers that contain granular activated carbon are the last step in the advanced oxidation process which quench or remove any remaining hydrogen peroxide from the UV-treated water.

VIEW LARGER Granular Activated Carbon (GAC) contractors at the Tucson Water AOP Water Treatment Facility. The towers that contain granular activated carbon are the last step in the advanced oxidation process which quench or remove any remaining hydrogen peroxide from the UV-treated water. SS: We did add four vessels, the original plant had eight vessels, we added four at a later date and that was after we discovered PFAS, we needed that to make sure we stayed below any existing health advisories at the time.

KM: In 2016, the EPA published lifetime health advisories and health support documents for certain PFAS contaminants with an advisory level of 70 parts per trillion.

SS: This plant was not designed to treat for PFAS which is why it was taken offline in 2021, from the potable system right and that was a precautionary measure on our behalf because we do not want to send anything out into the distribution system to protect our customers from any potential releases of PFAS.

[music fades in]

KM: In 2022, EPA published updated lifetime drinking water health advisories for PFOA and PFOS that took place of those from 2016.

KM: These interim levels indicated that some negative health effects may occur with concentrations of PFOA or PFOS in water that were near zero.

KM: EPA documents say Scientific studies have found that exposure to PFAS, even at lower levels, may result in adverse health impacts to the immune system, the cardiovascular system, human development and suppression of vaccine response.

KM: Studies have also linked exposure to adverse health effects on the liver, the kidneys and the immune system as well as cancer. Studies have found, following oral exposure, adverse health effects on the thyroid, reproductive organs and tissues and developing fetuses.

Will Humble: EPA sets standards for all of those kinds of chemicals, whether they are chemicals that are naturally occurring like arsenic which is already has been in drinking the groundwater for millennia from natural sources, or things like gasoline type chemicals, industrial solvents, in this case PFAS.

KM: That’s Will Humble. He is the executive director for the Arizona Public Health Association. Before that, he was the director of the state Department of Health Services for six years.

[music fades out]

WH: So EPA set standards for each of these and they’re the standards based on a toxicology analysis of how potentially harmful the chemicals are, either for acute health effects like liver problems or something like that or it could be the theoretical potential that a chemical can cause cancer and so they set standards that are protective of public health but they’re non-zero numbers.

KM: That's because getting a number to zero is basically impossible.

WH: So you have to have reasonable standards that people can meet that are still protective of public health but also recognize that there could be two, three, four parts per trillion PFAS in it. And I think people have to just recognize that by living in a post-industrial society, there’s going to be exposures to low levels of kinds of things that have been disposed of in the environment like these PFAS chemicals. I believe that the EPA standards are reasonable, the way they go about it is reasonable, some people in industry don’t think it’s reasonable because they think they should be allowed to have higher MCLs. There’s people, activists on the other side who feel like EPA is too permissive.

KM: Humble worked on the Superfund site declaration in the 1980s, and he says the contamination came from efforts around the time of the Vietnam War.

WH: And the long story short is what happened is that for many years those chemicals were being released into the soil and it got into the groundwater and the you know, the Tucson which at the time was reliant almost exclusively on the well water pulled that water out and delivered some of it to people and nobody really knew until about 1982 and that’s when the laboratory detection limits got much better with the new instruments that were becoming available in the 60s and then that’s when not just in Tucson, but across the whole country these solvents like TCE and PCE were discovered really in the early 80s. They were there for decades before that but laboratories were unable to detect it at that low concentrations.

KM: The Safe Drinking Water Act was passed by Congress in 1974 and authorizes EPA to set national standards for drinking water to protect human health against naturally-occurring and man-made contaminants.

KM: Those standards apply to public water systems and have been amended in the 80s and 90s.

WH: PFAS chemicals, there’s a theoretical, it’s a low level risk but there’s theoretical risk of increased causes of cancer, potentially liver damage, immune dysfunction, potentially developmental issues in kids. Again those kinds of health effects are really dependent on the exposure you get.

[music fades in]

LS: When I first started this organization, you know I had had enough. I started going door to door. I personally went to people’s doors.

LS: I moved away from the south side to get away from the problem and I ended up moving like three miles away, on the other side of Santa Cruz River…Within the three years after we moved in, all my children started getting sick.

LS: I started having children with birth defects in the early 1970s so it didn’t make sense to me that me and my kids are getting sick if we moved away from the southside to get away from the problem. So what I noticed is that many of my neighbors were also getting sick that had just moved in when we moved in. These were new houses.

KM: Linda says she started doing research at her local library around the time her granddaughter got sick in 2012. Doctors didn’t know what was wrong but believed she had leukemia.

LS: She was only two years old, and that’s when I said, ‘Enough is enough and I’m going to go back to the southside and I’m going to start researching because I want to know if they ever cleaned up that dirty water’.

KM: She says this problem didn’t start in the 80s, but even earlier when the Tucson Airport began its operations and community members could start smelling a foul smell coming out of their private water wells.

KM: Between the 1950s and the mid-1970s, TCE was used as a general-purpose solvent and degreaser at the Air Force Plant and airport. 1,4 dioxane was also used as a stabilizer to enhance the life of the solvent bath for degreasing manufactured parts. TCE, 1,4 dioxane, and other substances were disposed of at the plant and airport where they inevitably migrated into the groundwater.

LS: Stories that I heard from people when I did my door-to-door knocking project, I started across the street from the Tucson Airport. It only took me one minute to sit down and talk to a local Southside resident before they started listing the health problems in their families all believed to be a cause by the chemicals in the water. So you can imagine what that did to me.

LS: People were telling me that not only were they sick from the water from the pollution, they also said that their water that comes out of the faucet smell like poop. Nobody’s water should smell like poop. So when I was digging up more research, when I was hearing all these things right? So I’m trying to make sense of it all. I wanted you know I want to find out what happened. What happened to my daughter? Was my daughter murdered? Or was my daughter just sick and died?

[music fades out]

KM: Linda told me about an essay she read that was written in 2015 by a woman named Elizabeth Alvarado about her husband Fernando, whose parents moved into newly built homes around the airport in the 1970s.

LS: Sometimes there would be a rainbow line in the surface of his water. He said when he called the builder, he told us it was because it was a new home. He told us that he told us to keep the water running to clear out the pipes.

ZZ: So what happens once the water heads through the treatment plant? We'll hear after the break.

[mid-show break] –––––––––

ZZ: This is Tapped, a podcast about water. I'm ZZ.

KM: And I'm KM.

ZZ: Let's head back to the Tucson Area Remediation Project, where Tucson Water's Scott Schladwieller is taking us on a tour. The next stop, a portion of the facility that was built in 2023 that allows the company to deliver water the reclaimed water system.

SS: After we took this offline, we had to continue to treat water here 'cause the original intent here of course was to remediate TCE and 1,4 dioxane. TCE first and then 1,4 dioxane was added later, so even though we were concerned about PFAS, we still had an obligation and desire to remediate the aquifer for TCE so we had to continue treating it and after we thought about it, this was a great use of treated water to put this back in our recycled water system so what you see over here is a small tank where water’s been delivered from, comes directly out of the GAC treatment over into that tank where it splits. You see the booster station over here, that takes it over into the recycled water system where we built the pipeline across the freeway and tied into our recycled water system and then there’s also another outlet that goes back over and discharges into the Santa Cruz River right here and after that, that’s it for TARP but you know this water continues to flow throughout the system that is very highly treated water, very clean and we’re still continuing to make great use of it.

ZZ: You said the PFAS had to be kind of added on, was that like a change in the standards of what…acceptable levels of PFAS that caused the extension to have to happen or?

SS: So over time, the health advisories continued to drop, right? In 2016 there was an initial health advisory that came out and said these are the numbers that we need you to hit for for PFAS, for PFOA and PFOS. Over time those continued to drop, we of course had started testing regionally for PFAS in 2009, we didn’t really start seeing it here until about 2014, or so is when we started detecting it on the effluent side.

KM: Scott says this water doesn't go back into the potable water system, both because of the law and because it's not the right thing to do.

KM: And the next step is turning the TARP site back to its original purpose, removing TCE and 1,4 dioxane, and building an all-new treatment system for PFAS next door.

SS: Thanks to the state of Arizona and ADEQ we were given $24.9 million dollars to help construct the facility, that facility is, we should be seeing groundbreaking here in November or December of this year on that, plans are in with ADEQ for approval right now so we’re excited to see that come back online and that’s gonna help us out a lot and get back to the original intent of what this facility was designed for.

ZZ: Now there is a lot of talk that the federal standards for what’s acceptable as far as PFAS are going to go down, how much does that thought come into this planning that you might soon have to get the levels even lower because of that?

SS: So those are already in place, the EPA issued those MCLs, they came out in April and they were effective as of June 25, I think and then the way that works is that water providers have about three years to go out and do some initial testing and within about five years they have to have any processes in place to no longer serve PFAS to their customers. So that’s already being met here and it will continue to be met anywhere throughout our system, we’ve been very fortunate and all the other wells we have discovered PFAS in, we’ve been able to take those offline and still continue to provide service, however it’s starting to add up over time and we can’t do that forever and we have a few projects we have going around town where we are putting in treatment to bring back that lost capacity within our system.

KM: In a historic effort, this past April, the Biden-Harris Administration issued the first-ever national, legally enforceable drinking water standard to protect communities from exposure to forever chemicals like PFAS.

The rule sets limits for six PFAS to prevent thousands of premature deaths, tens of thousands of serious illnesses, certain cancers and developmental impacts to infants and children.

SS: There’s a lot going on, a lot of federal funding, a lot of congressionally directed, a lot of spending that’s coming our way, we are one of the most federally impacted communities I think in the country, when it comes to PFAS so we’re really working hard to protect everybody.

KM: Does Tucson Water, the state of Arizona and ADEQ absorb the operational costs of maintaining these facilities?

SS: No ADEQ right now has not, right now everything PFAS related has been on Tucson Water, we are of course working on a couple of different avenues to seek reimbursement for that, whether it’s depending on which responsible party we’re talking about and probably not going to get into that here but we are seeking reimbursement for that.

KM: He says they have received some funding from ADEQ and another state entity, the Water Infrastructure Finance Authority.

KM: EPA issued an emergency order for the TARP site, what changed here or what did that mean for Tucson Water?

SS: So the emergency order really kickstarted things, right? I mean there were timelines that were put on there, it’s not let’s figure it out over time, we’ve been talking about that for years already but the emergency order was EPA really saying, ‘hey there’s an immediate, imminent danger to Tucson's water supply so we want to see things happen at a much quicker place and they did put timelines in there which the Air Force and Air National Guard was to provide responses so that’s what we’re waiting to see at this point.

KM: In July, EPA issued a decision to finalize its Emergency Administrative Order, to the Air Force and Arizona Air National Guard.

KM: In their collective response for EPA to withdraw their order, the Air Force and Air National Guard state that they are fully committed to its ongoing PFAS response.

KM: Their case states that the Air Force paid $35 million dollars for the initial TARP Plant in 1991, and in 2016, paid $17 million dollars for the Advanced Oxidation Process facility.

KM: The Air Force argues that because the ADEQ and the City of Tucson have obtained tens of millions of dollars in federal grants, loans and loan forgiveness, including more than $50 million dollars from Biden-era infrastructure spending and another $12 million from the EPA, enough has been done to address PFAS cleanup.

KM: Last week the Air Force had a response, they served the EPA and said drop the order. What are your thoughts on that?

LS: The Department of Defense, by doing that basically they’re only doing it because they want to delay the process, they want you and which it’s wrong, it’s just devastating to us that they would even think of doing that.

KM: EPA follows the “polluter pays” principle when it comes to Superfund cleanup.

KM: Linda suggests that those who have been affected by contamination in Tucson, are the ones who pay the price.

LS: The reason why the water is bad is because they’ve contaminated our water. It’s been a man made disaster, they’ve caused this problem and unfortunately the people are the ones that pay for the cleanup, because when they built these facilities, that money comes out from the taxpayers, ratepayers money to pay to keep them open, maintained and operating.

[music fades in]

KM: When Linda’s daughter Tiana died, her daughter’s official death certificate said she died of pneumonia and natural causes.

LS: What child dies of natural causes?

KM: She decided to have an autopsy completed.

LS: I still wanted to know what killed my daughter and they said that her both kidneys, 19 years old, her both kidneys were shot 100%. 100%. And that’s the same stories I heard from other members in the community. Their death certificates were very similar to my daughter’s. Either they were pneumonia or natural causes, but really they suffered cancer, they suffered kidney cancers, they suffered leukemias. But that’s how they get away with it and then they never, they will never say that it was the water, you know the water was linked to the death or stuff like that. I thought if they did an autopsy on my daughter, they could find that she had TCE in her blood or in her body and it may be connected to her illnesses but they don’t even look for TCE.

KM: Linda met other advocates across the nation. They came together and founded the National PFAS Contamination Coalition to work on the problem at the federal level.

In April, she was invited to Washington D.C., when the EPA announced the finalized National Primary Drinking Water Regulation standards for PFAS.

LS: I’ve learned that working together is better than fighting. I’ve learned to be obedient, to serve my community, I’ve learned that it’s important for people to work together, especially because I had the opportunity to work with the federal government at that national level.

LS: President Biden, I love him, they did an amazing job on this project on the PFAS rule, I am more than satisfied with the work that they conducted. They were committed and they came through. He said he was going to do it and he came through with that promise.

[music fades out]

KM: AZPM reached out to the Air Force after the EPA’s initial emergency order was released. They sent us this statement, “The Department of the Air Force is committed to collaborating with our regulatory partners to protect human health and the environment. In that spirit we plan to meet with the Environmental Protection Agency to determine next steps. A record of the Department of the Air Force environmental program final documents for Air Force Plant 44 and Morris ANGB is available on the publicly available AF Administrative Record.

KM: AZPM is still waiting to hear back from EPA regarding the Air Force’s request for them to withdraw that order.

KM: For EPA to enact an emergency order, an “imminent and substantial endangerment to the health of persons” must be present.

KM: AZPM asked Tucson Water what the imminent and substantial danger was and they said, “The PFAS is polluting a sole-source aquifer and it would be uncontained and untreated if it were not for Tucson Water’s decision to step forward and address the issue prior to having any regulatory requirement to do so.”

[music fades in]

ZZ: Cleaning up Tucson's aquifers has been a major concern, but so has keeping them filled enough that the ground under the city doesn't subside.

For more than 20 years, it's done that by pumping its share of Colorado River water back into the ground.

So how does that water get to users who are hundreds of miles away from the river? The answer took decades of careful work and planning. That's next time.

Tapped is a production of AZPM News.

This episode was written and reported by Katya Mendoza and me, Zac Ziegler with audio mixing by me also.

It was edited by our News Director, Christopher Conover.

Our theme music and some interstitial music is by Michael Greenwald.

Visit our website in the podcast section of azpm.org for graphics, links and more.

Thanks for listening.

[music fades out]

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.